10 impressive innovations for cleaning up oil spills developed since the Gulf disaster

By Megan Treacy, Treehugger, 29 April 2015.

By Megan Treacy, Treehugger, 29 April 2015.

Over the five years since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, numerous new techniques, materials and approaches to cleaning up oil spills have graced the pages of TreeHugger. Most likely spawned by the immense need to find a better way to clean polluted water and land than using things like chemical dispersants, these ideas started being tested and developed.

Hopefully, when another disaster occurs, we'll be better prepared so that the impact is far less severe.

Here are 10 impressive innovations for cleaning up oil spills developed in the last five years.

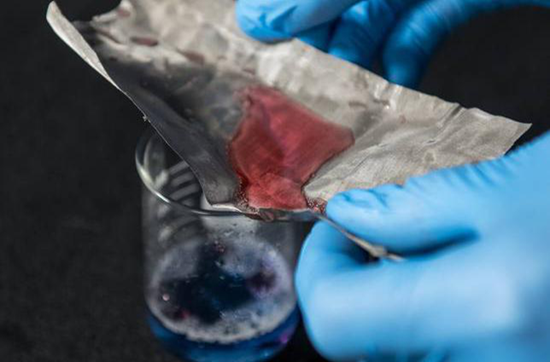

1. Smart filter that uses gravity, not chemicals, to separate out oil

Credit: Laura Rudich

Researchers at the University of Michigan believe that they have developed a next generation oil clean-up technology that could forgo chemicals and could clean-up water through gravity instead.

The smart filter technology is able to essentially strain the oil from the water because of a novel nanomaterial coating that repels oil, but attracts water.

To test the material, the team dipped postage stamps and small scraps of polyester in the solution, cured them with ultraviolet light and tested them in various oil and water mixtures and emulsions, including things like mayonnaise. Amazingly, with 99.9 percent efficiency the material was able to separate out all the different oil and water combinations.

2. Milkweed kits

Credit: pl1602

An amazing natural solution to oil spill clean up is the milkweed plant. Famous for being the sole food source for the monarch caterpillar, the plant has a super power that we're just discovering. The fibres of the seed pods of the plant have a hollow shape and are naturally hydrophobic, meaning they repel water, which helps them to protect and spread the seeds of the plant. But the surprising thing is that the fibres are also really great at absorbing oil.

In fact, the fibres can absorb more than four times the amount of oil that the polypropylene materials currently used in oil clean up can.

The Canadian company Encore3 has starting manufacturing oil clean-up kits using the milkweed fibres. The technology is made by mechanically removing the fibres from the pods and seeds and then stuffed into polypropylene tubes that can be laid on oil slicks on land or water. Each kit can absorb 53 gallons of oil at a rate of 0.06 gallons per minute, which is twice as fast as conventional oil clean-up products.

The kits are already being used by the Canada parks department for small oil spills on their sites and the bonus benefit of planting all of that extra milkweed for harvesting is that it helps support the endangered monarch butterfly.

3. MIT magnets that could pull oil from water

Credit: YouTube/MIT

In a typical oil spill clean up, the oil is burned or skimmed off the surface, but that process is inefficient at best and also removes any possibility of that oil being reused.

This new technique from MIT "would mix water-repellent ferrous nanoparticles into the oil plume, then utilize a magnet to simply lift the oil out of the water. According to a recent release, the researchers envision that the process could take place aboard an oil-recovery vessel, to prevent the nanoparticles from contaminating the environment. Afterward, the nanoparticles could be magnetically removed from the oil and reused. It's believed that this ability to recover and reuse the oil would offset much of the cost of clean-up, making companies like BP more willing to foot the bill for their mistakes."

4. Super absorbent polymer material

Credit: YouTube

Published in the journal Energy & Fuels in 2012, scientists from Penn State reported that they had demonstrated a "complete solution" for oil spill clean-up. It's a super absorbent polymer material that can soak up 40 times its own weight in oil. The material could then be shipped to an oil refinery for recovery of the absorbed oil.

The material that they call PETROGEL transforms the absorbed oil into a soft, solid oil-containing gel. The scientists say that one pound of the material can recover about 5 gallons of crude oil. It's strong enough to be collected and transported where it can then be converted to a liquid and refined like regular crude oil.

5. Lotus leaf-inspired oil-trapping mesh

The newest innovation in oil spill clean-up is this oil-trapping mesh developed by researchers at Ohio State University. The stainless steel mesh stops oil, but allows water to go through and its design was inspired by the lotus leaf.

Lotus leaves are covered in tiny bumps that are tipped with even tinier hairs, which cause water to bead up and roll off when it lands on the surface - oil, however, isn't affected in the same manner. The scientists altered the design of the mesh so that oil was repelled, but water was not.

Tests showed that when oil contaminated water was poured onto a piece of the mesh, the water flowed through while the oil was stuck on top. The researchers believe that large nets made from the mesh could be used to gather crude oil from sea water and then the oil could be used.

6. Roomba-like robots

Credit: YouTube

This idea for a helicopter-deployed Roomba-like robot called the Bio-Cleaner that could clean oil out of water is just a concept, but it's one we can get behind.

As Alex reported, "The yellow robot has three arms to propel itself. It has a built-in pump to separate out water, and a compartment with bacteria that degrades oil.

The cleverest part is an "acoustic wave device" that emits high-frequency sound waves designed to keep animals at bay, so they don't join the ranks of oil-soaked creatures that rarely survive."

We may not see this exact device helping clean up any oil spills in the future, but the design may very well inspire real-world solutions.

7. Pallets of clams

Credit: scott*eric

Instead of making a new material or robot, researchers at Southeastern Louisiana University are now looking into the oil cleaning abilities of the Rangia clam.

Since clams are bottom-dwelling filter feeders, the method by which they eat is what makes them excellent cleaners and they're already notable for their ability to make a dent in water pollution. The university is researching how the clams could intake oil-laced water, absorb the nutrients and oil, and then spit out clean water while keeping the toxic hydrocarbons in their bodies.

Of course clams are a food source for other marine animals, so the clams would be placed in a pallet that would allow them to clean the water without being accessible to other animals to eat.

8. Armies of microsubmarines

Credit: ACS Nano

These tiny technological marvels could propel themselves through water and absorb oil and when the job's done, gather at a collection area, guided by magnetic or electrical fields.

The microsubmarines are based on microtube engines that were created to deliver medicine through the bloodstream of the human body. The submarines are eight micrometres long - ten times smaller than the width of a human hair - and are propelled by an inner layer of hydrogen peroxide that reacts with the liquid they're submerged in to produce bubbles and shoot them forward. The submarines have a cone-shaped front end and are coated with a "superhydrophobic,” or extremely water-repellent and oil-absorbent, coating that helps them to glide through the water but also absorb any oil droplets along the way.

In small-scale tests, the microsubs were able to successfully gather and transport oil in water.

9. Autonomous sailboats

Credit: cesarharada.com

A team of inventors is developing autonomous sailboats that could be used to clean up oil spills, monitor water for radiation and even clean up plastic pollution - basically handle any environmental disasters that are too dangerous for humans to go clean up. The Protei Project has already started building these little boats and has even used them to take samples of river beds near Fukushima.

In the event of an oil spill, the sailboat's detachable boom could collect 2 tons of oil on each trip per boat, so with a swarm of them deployed, you could make an impact. While things in the ocean move downwind, the genius of Protei's design is that it can tack into the wind without loosing power, using a front rudder. It would start at the end of the oil spill and work upwards as the oil was blown toward it.

Right now the ships have to be controlled from shore, but the future versions will use algorithms to guide them through the water.

10. NASA's "frozen smoke"

Credit: NASA/JPL

Aerogel, also known as "frozen smoke", is a wonder-material that was first created by Samuel Stephens Kistler in 1931, and subsequently used by NASA to do things like capturing comet dust. The company that makes the material, AeroClay, has realized that the material could also be used to clean up oil spills through the creation of an Aerogel sponge.

The sponge would be able to absorb either water or oil, and its chemistry could be altered to do either. Because of its very low density, it could absorb far more oil than other materials. An Aerogel sponge could clean up oil covering rocks and birds like a kitchen sponge, but ideally it would be put in place to absorb oil from the water and keep it from reaching the shore.

![wpsCB70.tmp[4] wpsCB70.tmp[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhBOivUzaP5OsCXtWqjnlOk_ZtMgpiw56avh2WRdfVCWWmqyKthb5amibjxE-hDHr6jSJIQouYw3ZsmpBIc3WYupqBA_YtjK8SlsnDAPNQ5YuwawEbvfow8q5QHK3NTlng0A8hRR6hBU_wy/?imgmax=800)