BACKGROUND

Following the death of Prophet Muhammad s.a.w., the blessed Caliphs Abu Bakr, Omar, Uthman and Ali (known as Khalifah Rashidun or the “Rightly Guided” Companions of the Prophet s.a.w.) followed in his path, continuing to spread Islam, and a just order based on Qur’anic moral precepts, over a wider area. The enlightened reign of these four Companions is known as the Patriarchal Caliphate (632-661 AD). With the conquests achieved at that time, the Islamic Empire began expanding passed the boundaries of the Arabian Peninsula, growing as far as Tripoli in the west, Horasan in the east and the Caucasus in the north. The peoples in the conquered territories soon adopted Islamic moral values. The foundations of the new states to be founded were also laid during this period. The Patriarchal Caliphate was succeeded by the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750), and it was during the Umayyad reign that the Muslim conquest of Spain - one of the momentous events that shaped world history - took place.

At around 671 AD in Damascus, the Ummayads were trying to strategize how best to take Constantinople (Istanbul), due to it being the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire (or Byzantium, or 'Rum'). It was decided that the only way to take Constantinople was from the south (through Anatolia) and north (up through Spain, France, Italy, Romania and Hungary), and so Musa Bin Nusayr, the Governor of Northern Africa, was commissioned to begin the invasion of Europe to reach Constantinople through Spain.

Spain was then under the tyrannical rule of King Roderic of the Visigoths. Musa had not decided to proceed with a full scale land invasion of Spain until an opportunity presented itself. King Roderic had reportedly "kidnapped" and raped Count Julian's (the Governor of Ceuta in Northern Morocco, then still part of Spain) daughter who was sent to Roderick's court to be educated among the queen's waiting women. Julian vowed to Roderic, "the next time I return to Spain, I promise to bring you some hawks the like of which your Majesty has never seen!" Julian, a Christian, appealed to Musa for assistance in avenging Roderic for his crime, and hence take him out of rule.

Spain was then under the tyrannical rule of King Roderic of the Visigoths. Musa had not decided to proceed with a full scale land invasion of Spain until an opportunity presented itself. King Roderic had reportedly "kidnapped" and raped Count Julian's (the Governor of Ceuta in Northern Morocco, then still part of Spain) daughter who was sent to Roderick's court to be educated among the queen's waiting women. Julian vowed to Roderic, "the next time I return to Spain, I promise to bring you some hawks the like of which your Majesty has never seen!" Julian, a Christian, appealed to Musa for assistance in avenging Roderic for his crime, and hence take him out of rule.

In 710 AD, a preliminary intelligence collection mission was sent to survey the southern coastline of Spain, with the help of Julian, in order to gauge enemy capabilities and to designate a suitable landing spot for a subsequent larger raiding force to remove Roderic. The reconnaissance and subsequent test raid was successful and, after Musa got word of the mission’s success, decided to go forward with a full scale land raid into Spain. At this very moment, there was a fractious civil war underway in the Visigothic Kingdom, weakening army morale, reducing coordination of their forces and leaving them off-guard for a possible Muslim raid. Musa then called upon his young lieutenant to take charge.

That lieutenant was the fearless, legendary leader named Tariq ibn Ziyad. Tariq was born into the North African Berber tribe Nafzawah, and after the death of his father, joined the Muslim army in Northern Africa. As a young soldier, Ziyad had shown great skill in the army and had a strong Muslim faith. This was noticed by Musa ibn Nusair, who made him his deputy and appointed him the Governor of Tangier and Morocco. Tariq is known in Spanish history and legend as Taric el Tuerto (Taric the one-eyed). Tariq ibn Ziyad is considered to be one of the most important military commanders in Iberian history.

|

| Paintings of Tariq ibn Ziyad |

THE CONQUEST

|

| Jabal Tariq (Gibralter) |

Tariq and his Muslim Berber army had to cross the Strait of Gibraltar to begin the invasion of Spain. On April 29, 711 AD Tariq Bin Ziyad and his army landed at Gibralter (which is derived from the Arabic name Jabal Al Tariq which means Mountain of Tariq, or the more obvious Gibr Tariq, meaning Rock of Tariq).

The 17th century Muslim historian Al Maggari wrote that upon landing, Tariq burned his ships and then made a historical speech (well-known in the Muslim world) to his soldiers (there are several versions of the speech; the following is one of them):

"Brothers in Islam! We now have the enemy in front of us and the deep sea behind us. We cannot return to our homes, because we have burnt our boats. We shall now either defeat the enemy and win or die a coward’s death by drowning in the sea. Who will follow me?"

Tariq warned them that victory and Paradise lay ahead of them and defeat and the sea lay to the rear. It means defeat was not an option. After concluding his sermon, the Muslims themselves felt the vacuum of fear that had engulfed them disappear and now filled with courage and determination, a determination to win decisively.

|

| Painting depicting the burning of Tariq's ships |

The Muslim armies swept through Spain in a continuous northward thrust of raids deeper and deeper into Visigothic territory. After a series of raids in enemy territory a decisive engagement took place on 28th Ramadan 92 AH (19th July 711 AD) at the Battle of Guadalete, where Tariq defeated King Roderic, the last Visigothic ruler of Spain, at the Guadalete River in the south of the Iberian Peninsula. Tariq’s men had by then increased due to reinforcement sent by Musa. Whilst the Muslim army were largely comprised of foot soldiers, the Spanish army were fully armed with cavalry and horsemen. Due to internal strife within the Visigoth kingdom and the discipline of the Tariq's forces, the Muslim army easily defeated Roderic’s army almost without resistance. Roderick himself was never to be seen again, he had disappeared at some point during the battle, reportedly killed.

|

| Paintings depicting the Battle of Guadalete |

Victory was attained on 5th Shawal 92 AH (26th July 711 AD). Tariq sent the glad tidings to Musa who similarly informed the Caliph in Damascus. Musa then left his seat in Qairwan for Spain to join Tariq. Within seven years the conquest of the Iberian peninsula was complete. Muslim advancement continued further into Spain and into Southern France where it was halted after the Muslims were defeated at the Battle of Tours in 732 AD. After the conquest, Tariq was made governor of Spain but eventually was called back to Damascus by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I, where he spent the rest of his life.

|

| Al-Andalus after the conquest (in green) |

The Iberian peninsula under Muslim control was made a Wilayah (province) under the Ummayad Caliphate with the capital initially being in Ishbiliyyah (Seville), while Islamic law was established with the Christians and Jews being given their rights as Ahl Al-Dhimma.

Thus began the story of Islam in Europe and the Golden Age of Al-Andalus (or Andalusia) where Muslims ruled for over 700 years. It became one of the centers of Muslim civilization, and the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordova reached a peak of glory in the tenth century. Muslim rule declined after that and ended in 1492 when Granada was conquered by Ferdinand and Isabella.

|

| Rise and Fall of Al-Andalus |

THE GOLDEN AGE OF AL-ANDALUS

When we think of European culture, one of the first things that may come to your mind is the Renaissance. Many of the roots of European culture can be traced back to that glorious time of art, science, commerce and architecture. But long before the Renaissance there was a place of humanistic beauty in Muslim Spain. Not only was it artistic, scientific and commercial, but it also exhibited incredible tolerance, imagination and poetry. It was the Muslim civilization that enlightened Europe and brought it out of the dark ages to usher in the Renaissance. Many of their cultural and intellectual influences still live with us today.

Way back during the eighth century, Europe was still knee-deep in the Medieval period. That's not the only thing they were knee-deep in. This squalid society was organized under a feudal system and had little that would resemble a commercial economy. Medieval Europe was a miserable lot, which ran high in illiteracy, superstition, barbarism and filth. At first, Al-Andalus resembled the rest of Europe in all its squalor, but within two-hundred years the Muslims had turned Al-Andalus into a bastion of culture, commerce and beauty. By the beginning of the 9th century, Muslim Spain was the gem of Europe with its capital city, Cordoba in southern Spain. With the reign of Abdul Al-Rahman III - "the great Caliph of Cordoba" - came the golden age of Al-Andalus. Cordoba was the intellectual center of Europe.

Al-Andalus had a great cultural influence upon Europe until its demise in the late fifteenth century. Many historians who have studied Al-Andalus' influence upon Europe agree that this kingdom, with its social structure and high level of civilization, was far more advanced than the rest of Europe, and that it was one of the principle factors in the development of European civilization. The prominent Spanish historian Blanco Ibanez writes that:

"Defeat in Spain did not come from the north; the Muslim conquerors came from the south. This was much more than a victory, it was a leap of civilization. Because of this, the richest and most brilliant civilization known in Europe was born and flourished throughout the Middle Ages between the 8th and the 15th centuries. During this period northern peoples were shattered by religious wars, and while they moved about in bloodthirsty hoards, the population of Andalusia surpassed 30 million. In this number, which was high for the time, every race and religion moved freely and with equality, and the pulse of society was very lively." [Blasco Ibanez, A la Sombra de la Catedral, Madrid t.y., quoted in The Rise of Islam]

|

| The Splendour of Al-Andalus Cordoba |

With its well-illuminated streets, the capital Cordoba provided a striking contrast to the European cities and according to the English historian John W. Draper, "Seven hundred years after this time, there was not so much as one public lamp in London. In Paris, centuries later, whoever stepped over his threshold on a rainy day stepped up to his ankles in mud." [Quoted in The Rise of Islam]. At the same time, in Cordoba there were half a million inhabitants living in 113,000 houses, 700 mosques and 300 public baths spread throughout the city and its twenty-one suburbs.

During the end of the first millennium, Cordoba was the intellectual well from which European humanity came to drink. Students from France and England traveled there to sit at the feet of Muslim, Christian and Jewish scholars, to learn philosophy, science and medicine. In the great library of Cordoba alone, there were some 600,000 manuscripts.

This rich and sophisticated society took a tolerant view towards other faiths. Tolerance was unheard of in the rest of Europe, but in Muslim Spain, Muslims, Christians and Jews lived together in peace and harmony and flourished.

The Golden Age of Andalusian Science

Al-Andalus' contributions to Islam and the Latin West had been immense. Its intellectual contributions were largely in the field of mathematics, natural science and medicine. Arab-Muslim science in Al-Andalus flourished for several centuries. Its origin and rapid growth as a scholarly effort and as a state-supported institution could be traced to the 10th century patronization of scholarship initiated by Abdul Al-Rahman III (929–961 AD), founder of the Umayyad caliphate in Cordoba. He sought to create a new learning culture in Al-Andalus on the basis of the cultural and scientific achievements of Baghdad.

Although Muslims led and dominated the field of science and technology and were credited with most of Al-Andalus' scientific discoveries and innovations, the scientific enterprise in Andalusia was the result of collaborative efforts by Muslim, Jewish and Christian scholars and scientists. The period of growth and expansion in Andalusian science also witnessed the collaborative efforts of Muslim, Christian and Jewish scholars, researchers and translators in the production of new knowledge and in its cross-cultural diffusion. Jewish and Christian translators played an important role in advancing the ongoing Muslim synthesis, philosophical and scientific, and in the dissemination of Islamic science in their religious communities.

Al-Andalus had excelled primarily in botany and agriculture, astronomy and medicine. The leading botanists were Abu 'Ubaid al-Bakri and Ibn Hajjaj in the 10th century, Al-Ghafiqi and Ibn Al-Awwam in the 11th century, Abu'l-'Abbas al-Nabati and Abu Marwan Ibn Zuhr in the 12th century, and Ibn al-Baytar in the 13th century. They are among the greatest medieval botanists for their production of the period's most excellent writings on botany and agriculture. The Book of Agriculture (Kitab Al-Falahah) by Ibn Al-Awwam is considered the most important medieval work on the subject. It contained 34 chapters dealing with agriculture and animal husbandry. The book was also noted for its treatment of plant diseases and their remedies, and its pioneering attempt to discover a new soil science.

|

| Al-Ghafiqi |

Al-Ghafiqi was a renowned collector of plants in Spain and Africa. On the basis of this collection, he wrote about drugs and plants, which turned out to be the most accurate work in the history of Islam. In the words of writer George Sarton, Al-Ghafiqi was "the greatest expert of his time... His description of plants was the most precise ever made in Islam; he gave the names of each in Arabic, Latin and Berber." [Islamica Magazine]

|

| Ibn Al-Baytar |

Ibn Al-Baytar was perhaps the greatest pharmacist of medieval times. He was considered to have written the best work on the subject of simple drugs, with his description of more than 1,400 medical drugs as an outstanding encyclopedic work unsurpassed during the period. Abu'l-'Abbas al-Nabati, the botanist, was known for his writings on plants found along the African coast from Spain to Arabia.

It is quite clear that Andalusian botanists were interested in plants for their theoretical considerations and practical applications. The pursuit of botany was closely linked to the application of this knowledge to agriculture and medicine. Not surprisingly, Al-Andalus came to be noted for its advanced agriculture, unique botanical gardens and outstanding achievements in pharmacology. The Arabs introduced an ingenious irrigation system in Al-Andalus, thus allowing its agriculture to become the most advanced of the medieval period. Such elaborate irrigation systems supplied water to fields and gardens and, along with the advanced practice of agriculture and horticulture, Al-Andalus was able to modify the Persian garden "into a new form, which has survived to this day as the Spanish garden." Al-Andalus turned into one of the more advanced territorial space in the world. The agricultural development, thanks to innovative hydraulic technology and the introduction of new botanic species, allows not just the development of Arts and Science but that it changes the Iberian Peninsula landscape, impelling the creation of numerous sophisticated gardens.

|

| Paintings of Al-Andulas Gardens |

|

| Ibn Rushd (Averroes) |

Al-Andalus also excelled in medicine. It produced notable figures in Islamic medicine, each of whom authored the most advanced medical treatises of the time, thus helping to chart a new course for medical theory and practice. Interestingly, Al-Andalus' most famous philosophers were also physicians. Among them were Ibn Tufail, Ibn Rushd and the Jewish philosopher, Maimonides. Ibn Rushd (Averroes), better known as a commentator on Aristotle, was credited with several medical works including an encyclopedia entitled The Book of Generalities on Medicine, and his commentaries on Ibn Sina's medical works. Maimonides wrote 10 medical works, all in Arabic.

|

| Al-Zahrawi |

Al-Andalus' fame in medicine was gained through the work of Al-Zahrawi, the greatest Muslim figure in surgery. Kitab Al-Tasrif, the work that earned him the title "father of surgery," was translated into Hebrew, Latin and Castilian. The treatise on surgery is only one of 30 volumes of a medical encyclopedia treating all aspects of medicine and contained much that was original. It has been widely recognized in the Muslim world and the West as the "first independent surgical treatise ever written in detail." The work also included an unprecedented 200 pictures of surgical instruments, many of which had been invented by Al-Zahrawi himself. Included in the treatise are detailed descriptions of all known surgical operations and the instruments used in each of them. Of all medical works produced by Muslims, Al-Zahrawi's book was, until modern times, second only to Ibn Sina's Canon of Medicine in popularity among medical circles in the West.

|

| Ibn Zuhr |

Abu Marwan Ibn Zuhr, the most famous member of the Avenzoar family (known for its two generations of distinguished medical doctors) is also worth mentioning. He wrote several medical works, the most important of which is the Book of Diets. Historians of medicine generally consider him the greatest clinical physician produced by Al-Andalus. Taking the medieval period as a whole, he is ranked second only to Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi or Rhazes. In the field of pharmacology, which is closely related to botany and medicine, the works of Al-Ghafiqi and Al-Baytar were of general significance.

Related to medicine is the institution of hospitals and public health. Al-Andalus was famous for its chain of hospitals, which was considered the most advanced in medieval times. Hospitals were built in cities of Granada, Seville and Cordoba. It has been said that Cordoba alone had 50 hospitals and 900 public baths. At this time London was just building its first hospital. Not only were there more hospitals in the Islamic Empire than in Europe, but the medical treatment was usually far superior. Muslim hospitals had separate wards for different diseases, trained nurses and physicians and stores of drugs and treatments. As in other major cities in medieval Islam, hospitals in Andalusia also played an educational role not unlike that of our modern teaching hospitals. Most hospitals taught medical students and were inspected regularly to ensure that they are up to standard; students received a certificate to prove they had attended the training and had to pass an examination to get a licence to practise. Islamic hospitals had separate wards for different diseases, training wings, convalescent rooms for the aged and terminally ill as well as stores of drugs and treatments. Islamic hospitals were well organised with different wards for different types of illnesses, outpatient departments and theatres where medical students could attend lectures. Hospitals also looked after old people, especially if they had no families, and the insane.

|

| Al-Andalus Islamic Hospital in Granada |

|

| Jabir ibn Afla |

As for Andalusian achievements in mathematics and astronomy, leading astronomers were Abu'l-Qasim Al-Majriti, who lived in the 10th and 11th centuries, Al-Zarqali in the 11th century and Jabir ibn Aflah in the 12th century. Although Al-Majriti was an astronomer and alchemist, he was more famous for his Hermetical and occult writings. Nonetheless, he was an accomplished astronomer with several works on the subject to his credit. His writings include several commentaries on the astronomical tables of the famed mathematician from the East, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarazmi. He also commented on the Planisphaenum of Ptolemy and wrote a treatise on the astrolabe.

|

| Al-Zarqali |

But the person who should be regarded as the most outstanding astronomer from Andalusia is Al-Zarqali. He was an inventor who became famous for the safiḥa, a flat kind of astrolabe, which gained the attention of Western astronomers after detailed descriptions of it were published in Latin, Hebrew and several other European languages. As an observational astronomer, his most important contribution is the editing of the Toledan Zij (The Toledo Tables). This astronomical table, based on observations carried out in Toledo, was really the product of collaborative work Al-Zarqali had carried out with several Muslim and Jewish scientists. Like his safiḥa, the Toledo Tables attracted wide attention among astronomers in the Muslim and Latin worlds and were used by them for centuries. Copernicus, in his famous book De Revolutionibus Orbium Clestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), acknowledged Al-Zarqali's contributions to astronomy. In the theoretical domain, Al-Zarqali wrote the explicit proof of the motion of the apogee of the sun with respect to the fixed stars. He measured its rate of motion as 12.04 seconds per year, which is remarkably close to the modern calculation of 11.8 seconds.

An important development in Andalusian astronomy in the 12th century was the growing criticism that had been directed against the Ptolemaic planetary system. The first to express dissatisfaction with the system was Jabir ibn Aflah, followed by strong criticisms from philosophers such as Ibn Bajjah and Ibn Tufail, who were motivated by the intellectual need to defend the Aristotelian cosmological scheme. These criticisms did result in one or two new theories. Ibn Bajjah proposed a system based on eccentric circles, whereas Ibn Tufail presented his theory of spiral motion, which presented the system as one of homocentric spheres. Although these new theories did not find any practical applications, the Andalusian critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy left an impact on the minds of Renaissance astronomers.

Andalusian science is significant for our times: it shows that members of the three Abrahamic faiths (Islam, Jew and Christian) can work together to produce a common culture and civilization. It helped expand medieval science to new frontiers and influenced the development of science in the West during the Renaissance, which subsequently lead to the rise of modern science. For the contemporary Muslim world, Al-Andalus shows the way Islam can again be a source of inspiration for progress in science within the context of a pluralistic world.

|

| Some of the greatest scientific achievements of Al-Andalus and other Islamic centres |

The Splendor of Andalusian Art and Architecture

One quality acquired from Islamic teachings is the high sense of art and esthetics. The Qur'anic depictions of Paradise are pictures of the highest quality, finest taste, and stunning grandeur. Muslims had this sense of art in their hearts, which is reflected in their work, and thus the lands they ruled became the world's most modern and select regions.

Al-Andalus' capital city of Cordoba was full of amazing beauty with its clean, well-lit streets, libraries, hospitals, and palaces. In the same era, such great European cities as Paris and London were filthy, dark, and neglected. As a result, European Christians visiting Cordoba were amazed and dazzled by the city's splendor, culture, and art.

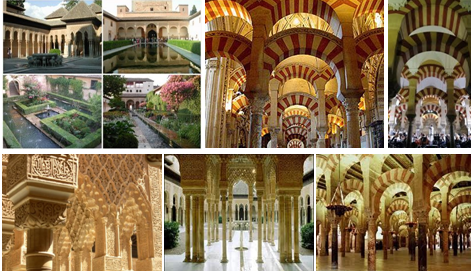

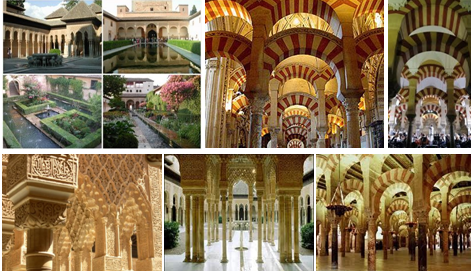

One of the few remaining examples of Cordoba's grandeur is the famous Cordoba Mosque, now a Catholic cathedral located in the city center. Originally it was a mosque of an esthetic style that captivated the minds of those who entered it. Christian explorers who came to Cordoba were deeply affected by this splendor. In the tenth century, a Saxon nun by the name of Hrotsvitha described Cordoba as the ornament of the world.

One of Andalusia's most spectacular buildings was the Al-Hambra palace, which was decorated with stunning examples of Islamic esthetics and art. Every detail reflected the same fine taste of Islam's higher spirit. Its gardens were full of fountains powered by a system based on gravity. The Muslims who built it were inspired by the Qur'anic depictions of Paradise, for example:

They will have preordained provision: sweet fruits and high honor in Gardens of Delight on couches face to face; a cup from a flowing spring passing round among them, as white as driven snow, delicious to those who drink, which has no headache in it and does not leave them stupefied. (Surah As-Saffat 37:41-47)

They will have Gardens of Eden with rivers flowing under them. They will be adorned in them with bracelets made of gold and wear green garments made of the finest silk and rich brocade, reclining there on couches under canopies. What an excellent reward! What a wonderful repose! (Surah Al-Kahf 18:31)

|

| Architectural Beauty of Al-Andalus |

CONCLUSION

The historical achievements of Al-Andalus show that Islam and Islamic morality played a leading role in the modern world's development. From the very beginning of its revelation, Islam has served as a guiding light, leading humanity to truth, reality, and beauty. The Muslims took their morality with them wherever they went, along with tolerance, reason, science, art, esthetics, hygiene, and prosperity. At a time when Europe was sunk in dark dogmatism and barbarism, the Islamic world was the world's most advanced and modern civilization. The values acquired by individual Europeans from the world of Islam played a fundamental role in developing European civilization.

On the other hand, one of the major reasons why the Islamic world fell behind in some respects was because it became estranged from the reason, sincerity, and open-mindedness taught in the Qur'an. This is because the Qur'an is the greatest source of guidance leading humanity out of darkness of ignorance and into the light of true knowledge. As Allah revealed to our Prophet s.a.w.:

Alif Lam Ra. This is a Book We have sent down to you so that you can bring mankind from the darkness to the light, by the permission of their Lord, to the Path of the Almighty, the Praiseworthy. (Surah Ibrahim 14:1)

Present-day Muslims should know the splendid past of Islamic civilization and honor the responsibility that comes with it. Let's not forget that Muslims are the representatives of a sacred, glorious, and honorable heritage that built one of the greatest civilizations on Earth. Moreover, they have always been envied and admired in equal measure by the representatives of other civilizations or religious denominations.

Muslims today should not just bask in the glory of their past, but must work to help the Islamic world rise once again. Of course Muslims can build a similarly splendid and world-illuminating culture and civilization again, but not until they recreate the spirit of unity and solidarity that drove their predecessors. If they can establish a democratic, constructive, tolerant, and peace-loving culture that works only for the benefit of Islam and humanity and disregards personal interests, they can build the greatest civilization of the twenty-first century.

Sources and Further Reading:

1. The Golden Age of Andalusian Science

2. An Incomplete History: Muslims in Andalus (Chapter 1)

3. The Moors: The Islamic West

4. A Call For An Islamic Union

5. The Rise of Islam

6. The Islamic Origins of Modern Science

7. Muslims and Scientific Thought

[Edited. Images added.]