Whether you're along the seacoast or in the middle of the U.S. Great Plains, there are few things more terrifying than really, really bad weather. Anyone who's experienced a hurricane such as Katrina in 2005 or Sandy in 2012 can testify to their destructive fury. While flooding is a serious problem, the most immediate threat from hurricanes is their powerful winds, which in a worst-case scenario can attain speeds of more than 150 miles (241 kilometres) per hour - enough to snap trees like twigs, knock down utility poles, rip off roofs and demolish house walls. Such a storm has the potential to render an area uninhabitable for weeks or even months [source: National Hurricane Centre].

Even inland, we still have to fear tornadoes - rotating columns of air that can suddenly strike a smaller area with winds ranging from 100 miles (161 kilometres) per hour to as much as 300 miles (482 kilometres) per hour [source: Jha]. A tornado that ravaged the town of Joplin, Missouri, in 2011 took 162 lives and caused an estimated US$2.8 billion in damage [source: Rafferty]. And according to scientists, these scary storms may become even more powerful in the future, thanks to climate change [source: NASA].

That's the bad news. But if there's a silver lining to those ominous dark clouds, it's that technology may help us to better withstand the destructive ravages of powerful winds. Here are a few of the most useful ways in which technology can save people from storms.

10. Supercomputers

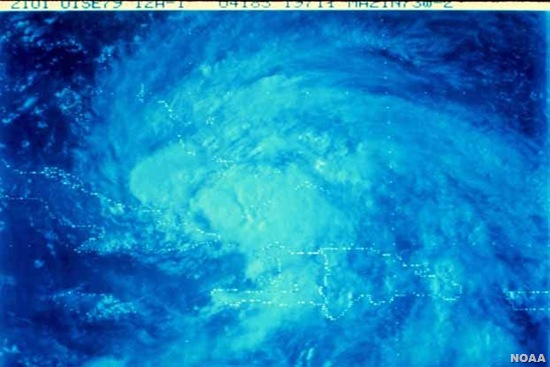

Satellite view of a tropical storm in the Caribbean area.

To understand how storms work and to anticipate their behaviour, meteorologists turned to a new forecasting tool in recent years: powerful supercomputers that create sophisticated virtual models of hurricane seasons. Before the summer hurricane season begins, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) now amass a vast amount of data from weather satellites and input it into a supercomputer at the Climate Prediction Centre in Gaithersburg, Maryland. A sophisticated computer program then simulates the interaction of the atmosphere and ocean in an effort to predict when storms will emerge, how big they will be, and how they will behave [source: Strickland].

Government weather forecasters are so convinced of the value of such modelling that they recently upgraded their supercomputers to be able to perform an astonishing 213 trillion calculations per second (about 200,000 times the speed of an iPad), and store 2,000 terabytes of data - roughly the equivalent of 2 billion digital photos. All that power has already improved the accuracy of their weather forecasting by 15 percent. The result is that people in hurricane-prone areas get a little more lead time to make preparations and evacuate.

As National Weather Service official Andy Nash explained in a 2013 interview, "Instead of maybe three days out knowing where [Hurricane] Irene was going to go, maybe its three-and-a-half to four days" [source: Borelli].

To help provide better data for the modelling, NOAA has a new array of weather satellites that take three-dimensional thermal images of the atmosphere [source: NOAA].

9. Better Weather Radar

Radar display of the Hurricane Fred centre.

Tornadoes are a scary threat - not just because they kill hundreds of people in the U.S. each year, but because they long have been notoriously difficult to predict and track. But National Weather Service forecasters are now using a technological advance that they hope will enable them to better predict where tornadoes are headed.

The service's existing NEXTRAD radar system has long relied upon 150 massive radar antennas spread across the country, which sit on dedicated towers several stories high, and track storms that are more than 100 miles (162 kilometres) away. But the old system has limitations. Because the pulses of electromagnetic radiation that the antennas send out travel in straight lines, the Earth tends to block their view of anything that's far away and also close to the ground. That works out to a blind spot that covers about 75 percent of the atmosphere below 1 kilometre (0.62 of a mile) in altitude, which is where a lot of weather occurs.

CASA (Collaborative Adapting Sensing of the Atmosphere) radar, a system developed by a consortium of universities, tries to fill in that coverage area with a vast number of smaller antennas attached to buildings and cell towers. In a 2011 test, researchers found that CASA helped them to see that a tornado in the Chickasha, Oklahoma, area was veering north, and to direct first responders to the stricken area within minutes [source: Hamilton].

8. Cyclone-proof Roofs

This house was left roofless (and missing some walls) after a tornado touched down in Kentucky.

During a powerful storm, one of the biggest risks is having the roof ripped off your house. The powerful winds blowing over your home will exert inward pressure against the far wall that's downwind, push outward against the opposite wall and the side walls, and push the roof upward. If your roof beams aren't strongly connected, the roof will lift off, leaving your house's walls without any lateral stability or bracing. That, in turn, will cause them to collapse outward, so your house will appear to explode [source: DeMatto].

This happens a lot, particularly when tornadoes strike. Outside of hurricane zones, most building codes only call for roof trusses to be connected to the top of exterior walls with 3.5 inch (9 centimetre) nails. Those connections are enough to withstand brief gusts of wind at speeds of up to 90 miles (145 kilometres) an hour. But even an EF1 tornado (the smallest class of twister) is going to have much more powerful wind [source: Hadhazy].

In the future, you may be able to buy a house built from super-strong carbon fibre or from Kevlar, the material used in bulletproof vests, which could survive such forces unscathed [source: Fox]. But in the meantime, you can install galvanized-steel "hurricane clips," which brace portions of the trusses or rafters in a house. These strengthen the roof so it can withstand battering by 110-mile-an-hour (177 kilometre-an-hour) winds. A 2,500-square-foot, two story house can be equipped with clips for around US$550, including labour [source: DeMatto].

7. Storm-resistant Doors

A steel door could protect your home from getting blown in.

Even if your house isn't knocked down by a powerful storm, your front entrance can take a real beating. That's not a good thing, especially if you're hoping to remain safe from the weather and also from looters who sometimes take advantage of a weather disaster.

Texas Tech's Wind Science and Research Centre actually tests doors for storm resistance, using a giant air bladder that simulates up to the force of an EF5 tornado, the most powerful twister around. (Here's a list of doors that they've tested.) One state-of-the-art product, Curries' StormPro 361 door and frame assembly, is essentially a door-within-a-door, with a 10-gauge steel hollow exterior that contains a layer of polyurethane cushioning and a second layer of steel inside [source: Rice, DeMatto].

But that US$5,500-plus door could go to waste if you've got another, bigger vulnerability - an interior garage with a slide-up garage door. Such doors are notoriously flimsy, and if yours fails during a tornado, you'll get a lot of internal pressure inside your house that potentially could blow out your walls and ceilings.

Protect against this by picking a good stiff garage door, and hiring a technician to add weights to the door's counterbalance system. This will make it less prone to roll up in strong winds [source: FLASH]. You can also buy a specially designed bracing system such as Secure Door [source: DeMatto].

6. Unbreakable Walls

Housing developer Scott Chrisner demonstrates the ICF wall, special foam-insulation blocks

with concrete poured inside.

Even if your roof and doors don't give way in a tornado or hurricane, powerful winds are going to push against your walls directly - and possibly slam big pieces of debris into them at 200 miles (321 kilometres) per hour. So if you want a storm-resistant house, you've got to have tough walls as well.

Fortunately, back in the late 1960s, an inventor named Werner Gregori developed a new technology: insulating concrete forms, or ICF, that use polystyrene forms which clamp together in tongue-and-groove fashion, with plastic or steel connectors [source: ICF Builder]. Try to imagine really big, tough Lego blocks, and you'll get the general idea. Once the building blocks are set, a steel framework is put in to for reinforcement, and concrete is poured into the plastic forms. The result is an airtight, insulated, fire-resistant 2-foot (61-centimetre) thick wall that's sturdy enough to withstand strong winds [source: DeMatto].

One such tornado-wall system, the ARXX ICF wall, is designed to withstand objects propelled by a 250-mile-per-hour (402 kilometre-per-hour) wind [source: ARXX].

ARXX claims that using ICF technology isn't that much more expensive than using conventional wood and mortar and that it actually will reduce your heating and cooling costs drastically, because an ICF building typically uses 44 percent less energy to heat and 32 percent less to cool [source: DeMatto].

5. Shatter-resistant Windows

If your windows are shatter-resistant, it means that even if they break, pieces of glass won’t go

flying around the house.

There's an old myth that opening your windows during a tornado or hurricane will equalize the pressure inside and outside the home, allowing the storm to pass through your house without destroying it. Unfortunately, that's not how it works. An open window only allows a clear path for high-speed debris, and can actually cause the house to become even more pressurized [source: DeMatto]. So you want your windows shut during a storm. But you don't want them to shatter and send razor-sharp shards of glass flying at you, either.

One solution is to use impact-resistant glass. (In places such as south Florida, where hurricanes are a continual threat, building codes already require you to do this.) There are two common types of shatter-resistant glass. The first is composed of two sheets of glass separated by an inner plastic membrane. That makes the window stronger against even repeated battering, and the membrane keeps the pieces from flying all over the place if the window does shatter. The second type uses a plastic film applied to the outer surface of the glass to catch fragments, but it's not quite as sturdy [source: Flasch].

Shatter-resistant isn't necessarily shatterproof. That's why for good measure, you'll want to shutter your windows with plywood. Instead of nailing the wood in place, use a product such as the PlyLox Window Clip, which lodges into the corners of the window opening, and resists being pushed out. In tests, the clips withstood impact and wind pressure of up to 150 miles (241 kilometres) per hour [source: DeMatto].

4. Tie-down Systems for Structures

For extra protection, consider a cable system that ties the house frame to the foundation.

Back in 1921, a powerful cyclone swept into the village of Mint Spring, Virginia, and tore a frame house belonging to the Ballew family clean off its foundation, lifted it into the air for a second, and then flung the house into the ground, about 50 feet (15 meters) from its original location. The matriarch of the family, who had been inside the house, was found in the wreckage, unconscious but still alive, and her young son was similarly found alive a short distance away in a field, according to a local newspaper [source: News Leader].

Engineers have calculated that it only takes a wind speed of 105 miles (169 kilometres) per hour - about what an EF1 tornado achieves - to create enough uplift or vertical suction to pull a roof off a house [source: Kennedy].

Of course, this is not something that you want to happen to you. That's why you might consider using a cable system such as Cable-Tite to attach the top of your house's frame to the foundation. You can tighten the cables to create a continuous downward pressure on your home. This is designed for use with new construction or a major renovation [source: Cable-Tite].

3. A Smarter Electrical Grid

Much like a smartphone has a computer built in, a smart grid has everything associated with the

electrical network computerized.

Even a thunderstorm is often enough to knock out electrical power in some places. And a major storm is much worse. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy knocked out the lights for 8.5 million people on the East Coast, and a month after the storm, roughly 36,000 people in New York and New Jersey still were without electricity [source: Scott].

But the problem of storm-related power outages could be lessened if utility companies replaced the present antiquated electrical transmission system with "smart" grids, equipped with a vast array of computerized sensing and control devices to monitor power demand and system performance to distribute electricity more efficiently. The "grid" refers to the electrical wires, substations and transformers that help generate electricity, and much like a smartphone has a computer built in, a smart grid has everything associated with the electrical network computerized with two-way digital technology [source: Dept. of Energy]. Instead of relying exclusively upon central power plants and transmission lines, smart grids can also tap into local sources of electricity, such as solar panels and wind turbines.

Because of their sensing abilities, smart grids enable utility companies to spot and repair damage after storms more quickly. They also allow decentralized storage and power generation, so that local neighbourhoods cut off from the main lines can still have some access to electricity. Several cities and states in the U.S. are already implementing smart grids or seeking funding to do so [source: Hardesty, Kingsbury].

2. Emergency Weather Radio

Weather radios typically have hand cranks and/or solar panels, so you can recharge the battery

even without electricity.

Even if you manage to ride out a hurricane safely, you're likely to be confronted with another problem: an inability to find out what's going on outside of your immediate neighbourhood. Above-ground phone lines are often knocked down by winds, and cell towers and broadband Internet and cable TV connections are vulnerable to disruption as well.

Being cut off from weather bulletins in such a crisis can put survivors at even greater risk. That's why it's advisable to have a weather radio which has a special receiver capable of picking up NOAA broadcasts at VHF (very high frequency) channels, which cannot be heard on an ordinary AM/FM radio [source: NOAA]. The radios typically have hand cranks and/or solar panels, so you can recharge the battery even without electricity. Some models also feature alarms to alert rescue searchers, flashlights and cell-phone chargers. Prices range from US$20 to US$200 [source: Consumer Reports].

1. Old-school Telephones

Don't underestimate the power of a good old-fashioned landline.

Remember the good old days, when everybody had a simple copper phone line running into his or her house and wall jacks where the phone plugged in? And the phones themselves had curly cords that attached the receiver to the body, and didn't need batteries?

Americans have rapidly shifted away from that quaint old technology in favour of wireless cell phone connections and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) phones that use broadband fibre-optic cables and convert conversations to digital information, just like Web sites or e-mail.

Since 2000, when the number of old-fashioned copper phone lines in the U.S. peaked at 186 million, about 100 million of them have been disconnected, and today just one in four American households still has a copper wire connection. Phone companies are finding them too costly to maintain with the dwindling demand for landlines [source: Svensson].

The problem is that while those state-of-the-art phone connections may seem superior when the skies are sunny, in a weather emergency, they often are knocked out of commission. Worse yet, the batteries in cordless and cell phones eventually run out of juice. The old-fashioned phones that plug into copper lines, in contrast, usually work fine, as long as the line isn't on a telephone pole that gets knocked down by the storm [source: Grgurich]. That's why you should keep an old-fashioned phone around for emergencies. Unfortunately, it may not be an option that you'll have for much longer, but take advantage of it while you can.

Author's Note: I've always found powerful storms to be extremely frightening, ever since I was a five-year-old on a Sunday drive with my parents, and we heard a tornado warning on the radio that described how the cyclone would resemble an elephant's trunk. All that day, I sat in the backseat and peered through the windows, watching for that scary shape in the sky. Many years later, I had to travel to the Florida panhandle to report on the aftermath of a powerful hurricane, and I was astonished to see the bizarre destructive effects of such a storm - a half-demolished house, for example, where the Venetian blinds in the windows of one of the surviving walls were twisted into strange DNA-like double helixes. Having talked to people about the terror of riding out such a storm, I'm glad to see that technology may help reduce the carnage from future weather catastrophes.

Article Sources:

1. ARXXICFs. "ARXX ICF Wind Test & Storm footage." Youtube.com. April 28, 2012. (Aug. 25, 2013)

2. Borelli, Nick. "How Supercomputers Are Improving Weather Forecasting." Wcax.com. Aug. 15, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

3. Cabletite.com. "Engineered for High-Wind Uplift Home Protection. Cabletite.com. Undated. (Aug. 25, 2013)

4. Consumer Reports. "An emergency weather radio can get you through the storm." Consumerreports.org. Aug. 28, 2012. (Aug. 25 2013)

5. DeMatto, Amanda. "8 Ways to Protect Your Home Against Tornadoes and Hurricanes." Popularmechanics.com. June 2011. (Aug. 25. 2013)

6. Department of Energy. "Smart Grid." Energy.gov. (Aug. 25, 2013)

7. Federal Alliance for Safe Homes. "Tornadoes: Garage Door Securing." Flash.org. 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

8. Flasch, Jim. "Hurricane-Proof Your House with Impact-Resistant Windows." Bobvila.com. Undated. (Aug. 25, 2013)

9. Fox, Stuart. "Futuristic Materials Could Build Tornado-Proof Homes." Techewsdaily.com. May 24, 2011. (Aug. 25, 2013)

10. Grgurich, John. "AT&T Wants To Cut the Cord on Your Landline Phone." Dailyfinance.com. Nov. 13, 2012. (Aug.25, 2013)

11. Hadhazy, Adam. "Gone in Four Seconds—How a Tornado Destroys a House." Popularmechanics.com. Undated. (Aug. 25, 2013)

12. Hamilton, Jon. "Advanced Tornado Technology Could Reduce Deaths." NPR. June 17, 2011. (Aug. 25, 2013)

13. Hurricane Hotline. "Save Lives With Hurricane Clips." Hurricanehotline.org. (Aug. 25, 2013)

14. ICF Builder Magazine. "History of ICFs." 2010. (Aug. 25, 2013)

15. Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. "FORTIFIED Home." Disastersafety.org. (Aug. 25, 2013)

16. Jha, Alok. "Tornadoes: Where does their destructive power come from?" The Guardian. April 28, 2011. (Aug. 25 2013)

17. Kennedy, Wally. "Civil engineers release study of Joplin tornado damage." Joplin Globe. June 8, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

18. Kingsbury, Alex. "10 Cities Adopting Smart Grid Technology." US News. (Aug. 28, 2013).

19. NASA Earth Observatory. "The Impact of Climate Change on Natural Disasters." Nasa.gov. (Aug.25, 2013)

20. National Hurricane Center. "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale." Nhc.noaa.gov. May 24, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

21. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "New satellite instrument for improved weather forecasts put into service." Noaa.gov. Feb.8, 2012. (Aug. 25 2013)

22. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "NWR Receiver Consumer Information." Aug. 2, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

23. National Wind Institute. "Protection from Extreme Wind." Ttu.edu. Undated. (Aug. 25, 2013)

24. News Leader. "1921 Tornado Strikes County Village." Aug. 23, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

25. Nosowitz, Dan. "Can You Tornado-Proof A Home?" Popular Science. May 31, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

26. Pittsburgh Corning. "LightWise Architectural Systems Tornado-Resistant Windows." (Aug. 25, 2013)

27. Rafferty, Andrew. "Six of the Worst Twisters in U.S. History." NBC News. May 21, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

28. Renauer, Cory. "Hurricane Sandy, Smart Grids and Advanced Storage Technology." The Energy Collective. Nov. 2, 2012. (Aug. 25, 2013)

29. Rice, Doyle. "Making a Home Tornado-Proof is Tough." USA Today. Apr. 4, 2011. (Aug. 25, 2013)

30. Sasso, Brendan. "FCC says Hurricane Sandy knocked out 25 percent of cell towers in its path." The Hill. Oct. 30, 2012. (Aug. 25, 2013)

31. Scott, Amanda. "Hurricane Sandy-Nor'easter Situation Reports." Energy.gov. Dec. 3, 2012. (Aug. 25, 2013)

32. Sheasley, Chelsea B. "Mammoth Oklahoma tornado was widest ever recorded - almost strongest, too." Christian Science Monitor. June 4, 2013 (Aug. 25, 2013)

33. Smith, Gerry. "AT&T, Verizon Phase Out Copper Networks, 'A Lifeline' After Sandy." Huffingtonpost.com. Nov. 9, 2012. (Aug. 25, 2013)

34. Strickland, Eliza. "Satellites and Supercomputers Say 6 to 10 Hurricanes Coming." IEEE Spectrum. June 1, 2011. (Aug. 25, 2013)

35. Svensson, Peter. "Telephone companies to abandon land lines." Salon.com. July 9, 2013. (Aug. 25, 2013)

Related Articles:

Top image: A startled man gets ready to run after a hurricane-driven wave smashes into a seawall in 1947. See more storm pictures.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.