Amended: 10 Things That Ended Up In The Completely Wrong Place

By Alan Boyle, Listverse, 12 June 2014.

By Alan Boyle, Listverse, 12 June 2014.

Some things aren’t where they should be. For example, you can go to Scotland to see wallabies or check out the huge camel population of Australia. These 10 things will do the same job of making you exclaim “What on Earth is that doing here?”

10. Manhattan’s Floating Farmhouse

Photo credit: Beyond My Ken

Homes in Manhattan tend to be tall and made of brick. In fact, building houses from wood was banned in the 19th century to prevent fires. That’s why the wooden house on 203 East 29th Street looks like it’s from the 18th century. It’s almost like a three-story farmhouse flew in from the countryside, landed on top of a brick building, and squashed it.

There’s a lot of mystery surrounding the house’s origin. A house of some sort was noted at that location in 1840, and a three-story house was recorded on tax records in 1860. By 1880, it had increased to four floors. The wooden house may have been raised and fortified with a shallow brick floor, which would explain why its front door is on the second floor.

The house later found a few decades of use as a junk shop, where metal, rubber, rope, and paper was bought and sold. In 1979, it was restored and returned to private residential use.

9. Seattle’s Lenin Statue

Statues of Vladimir Lenin are common throughout the former Soviet Union. One example is a bronze statue by sculptor Emil Venkov that was erected in 1988. The 5-meter (16 ft) sculpture of the communist revolutionary was put up in Poprad, a Slovak town that was then part of Czechoslovakia. Just a year later, with the USSR crumbling, it ended up in a local garbage dump.

It was spotted by an American businessman named Lewis Carpenter, who took a liking to its artistry. Carpenter mortgaged his house to buy the statue and shipped it to Seattle. When he was killed in a car accident in 1994, Carpenter’s family loaned the statue to the neighbourhood of Fremont, Seattle. It’s been up for 20 years, technically for sale. Today, you can buy it for US$300,000.

The statue has been a controversial landmark. A Facebook page titled “Seattle, Tear Down this Vladimir Lenin statue!” declares that he has “NO PLACE IN AMERICA!” Fremont justifies its presence as a “symbol of an artistic spirit that outlasts regimes and ideologies.”

8. Mo‘ynaq

Photo credit: Albert Herring

Uzbekistan has an entire town that looks completely out of place. The town of Mo’ynaq was once a thriving fishing town that was home to tens of thousands of people. Today, it’s a desert, 88 kilometres (55 mi) away from the sea. It’s a casualty of the USSR’s draining of the Aral Sea. The water that’s left in the town to drink is heavily polluted, and mortality is 30 times greater than it used to be.

Yet the town still has its fishing fleet, dozens of boats deteriorating on the sand. The town’s welcome sign has a logo of a fish jumping from the water, and there’s a billboard on the roadside with a painting of smiling fishermen in overalls pulling a catch from the sea. There’s still a fish-canning factory, thought it’s used less than the graveyard of ships, which has become a makeshift playground for local children.

7. Viaduct Petrobras

Photo credit: Fabio Musarra

The Viaduct Petrobras is an elevated stretch of highway that sits 40 meters (131 ft) above the Brazilian jungle. It was built in the 1960s and ’70s to be part of the Rio-Santos Highway but abandoned after a last-minute route change in 1976. The jungle quickly closed in, leaving the 300-meter (984 ft) road standing there, having never been joined to anything.

Ironically, it can’t be reached by car. You can get close on a thin country road, but the rest of the journey must be walked. A rudimentary wooden staircase is the only way up. This has turned the failed roadway into a surprising tourist attraction. If you dare make the climb as part of an organized tour, you can even rappel into the canopy below.

The viaduct is one of several construction projects that were lost to the jungle during the construction of the BR-101 highway. There are tunnels, walls, and foundations hidden elsewhere among the foliage. In the early 2000s, the mayor of Sao Sebastiao sent a letter to Brazil’s transport minister asking them to finish construction. The town is on the coast and would have been bypassed by the original route but now faces frequent traffic problems.

6. The Reading Pagoda

Photo credit: Andy Gaskin

In 1906, a businessman named William A. Witman had a plan to build a luxury resort on Mount Penn, just outside of Reading, Pennsylvania. The centrepiece was a seven-story pagoda, finished in 1908. Within two years, the resort plan had fallen apart, as Witman was unable to acquire a liquor license. On April 21, 1911, the building was given to the city. The pagoda has become a symbol of the city, which has an Asian population of just 1.2 percent, half the state average. At one time, lights on the structure were used to communicate messages in Morse code, including the results of sporting events.

While the pagoda may appear out of place from the outside, the real oddity is inside. The pagoda is home to a bell that was cast in Obata, Japan in 1739. It used to be part of a Buddhist temple called Choshoji. The temple was in the city of Hanno, now part of Tokyo, but has since been demolished. All documentation on how the bell ended up crossing the Pacific has been lost. Some relics from Choshoji are preserved and still worshiped in another temple nearby. The chief priest there would like to add the bell to their collection but expects that returning it to Japan would be “impossible.” At the very least, he hopes that the city of Hanno could become a sister city of Reading.

5. Colonia Tovar

Photo credit: Rjcastillo

Colonia Tovar has been called the “Germany of the Caribbean.” It seems like a contradiction, but it’s impossible to overstate exactly how German the town is. It has the architecture of a Bavarian mountain village and the cuisine to match. It may be the most authentic piece of Europe in South America, and it’s due entirely to Colonia Tovar’s odd history.

The town was founded in 1843 by an Italian cartographer named Agustin Codazzi. When the Venezuelan government started looking for immigrants to revitalize their economy, Codazzi found a suitable spot and recruited 376 Germans. By the time they got there, the government had lost interest, and they were left living in an isolated spot of the jungle.

They built a town to look as much like their homeland as possible and cut themselves off from the surrounding area’s culture for a century. Until 1940, residents weren’t allowed to marry outsiders, and there wasn’t a road to Colonia Tovar until 1963. Today, its population is growing, and it’s often filled with tourists.

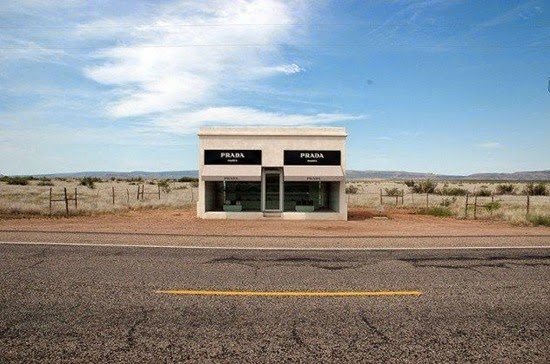

4. Prada Marfa

Photo credit: Marshall Astor

In 2005, Texas got its first Prada store. It was stocked with items from that year’s fall collection, including shoes handpicked by Miuccia Prada herself. It’s been visited by celebrities like Beyonce, yet it’s never been opened, and it’s located on a roadside many miles from civilization.

The store was built as an art piece, meant to be a critique of luxury goods. It was vandalized three days after opening, and its inventory was stolen. It was repaired and given a better security system, yet its future looks bleak. It’s been vandalized again, this time on a larger scale. The artists plan to restore it, but they face a bigger problem.

In 2013, the building was classified as illegal roadside advertising by the Federal Highway Administration. The 1965 Highway Beautification Act forbids the use of company logos by the roadside without a permit, and the transportation department has promised to take action. Some people, including the artists behind Prada Marfa, see this as needless bureaucracy, especially since the piece was there for eight years before anyone had a problem with it.

3. Buildings In The Middle Of Roads

Photo credit: Richard Harvey

There are two ways for structures to end up in the middle of a public highway. One is by mistake, like when miscommunication led to a telephone pole sticking out of the tarmac on a road in Quebec. A more common problem is stubborn homeowners who refuse to move to make way for new highways.

Stott Hall Farm is a well-known example in England. When the M62 motorway was built in the 1970s, farmer Ken Wilde refused to give up his farm. Despite having the legal power to force a purchase, the council gave in and split the carriageways around the house. Today, the farm sits in the middle of the road, with a tunnel under the tarmac for exiting safely.

Likewise, Chinese authorities clashed with retiree Luo Baogen and his wife over a road project, but they didn’t have a farm. Their house was part of a larger building. Unlike England, the Chinese government can’t legally force people to sell, so they simply knocked down the building around Luo’s section and surrounded it in a circle of tarmac. Traffic is directed straight at the house before swerving tightly around it, literally inches from the walls.

2. London Bridge In Arizona

Photo credit: Aran Johnson

In 1831, a new bridge was built across the Thames in London. It was designed by a famous civil engineer, John Rennie, and built from 130,000 tons of granite. There had been a London Bridge on the site ever since the Romans ruled England, and the last one had survived for 600 years. At one point, the infamous medieval bridge had 200 buildings along its length.

Rennie’s bridge was built to deal with the traffic of a much busier city, but it soon began to sink. By 1967, the bridge was no longer sustainable, and it was put up for sale. The buyer was Robert P. McChulloch, an American businessman who paid US$2,460,000. A year later, the bridge was broken up and shipped to Arizona. It was rebuilt in Lake Havasu City to be the centrepiece of a British theme park, where it still sits today.

1. Madrid’s Real Egyptian Temple

Photo credit: Andrew J.Kurbiko

With all the trouble in Egypt, you might be looking for a safer place to see a piece of original ancient Egyptian architecture. Luckily, Madrid is home to the Temple of Debod, built 2,200 years ago by the Egyptian King Adikhalamani. It’s the oldest monument in the city by a large margin. Madrid’s original walls only date to the ninth century, making them over 1,000 years younger than Debod.

The story of how an Egyptian temple ended up in Spain is a fascinating one. In the 1950s, Egypt’s population was on the rise, so the country needed to increase agriculture and energy generation. The solution was the construction of a giant dam, which led to the creation of one of the world’s largest man-made reservoirs, Lake Nasser. Unfortunately, this meant that large numbers of monuments were going to be submerged, including Debod. Archaeologists rushed to save them in the few years they had, and Debod was taken apart and its blocks put in storage.

The temple was donated to Spain in 1967 as a token of gratitude for financial assistance to Egypt. The pieces of the building were transported by barge, ship, and truck. The last of 1,350 boxes arrived in Madrid on June 28, 1969, and the temple was put back together over the course of three years. If you’re happy with something a bit smaller, however, there are always the obelisks in New York and London.

Top image: A big fishing boat sitting on the Aral seabed near Mo’ynaq, Uzbekistan. Credit: upyernoz/Wikimedia Commons.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.