7 Communities Who Salvage Trash to Survive in the World's Dumpsites

By Yohani Kamarudin, Environmental Graffiti, 2 July 2012.

By Yohani Kamarudin, Environmental Graffiti, 2 July 2012.

Extreme weather, toxic substances, foul odours, stray animals, disease, flies, and the general disdain of other sections of society - these are just a few of the hazards and hardships the rag pickers and refuse salvagers who live and work on dumpsites in poorer parts of the world must contend with daily. Yet the work they do - sorting through garbage and reclaiming whatever is usable - is both honest and worthy of respect.

Birds circle as people toil on the garbage mound of Gramacho, Rio de Janeiro. Photo: Ben Lievens

These people are grassroots recyclers - scavengers who give a second life to the plastics, glass, metals and other materials and objects they collect which would otherwise go to waste.

A boy finds a toy in a mountain of trash in Dharavi, India. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica

Here we look at seven communities in different parts of the world that make their living by reclaiming the bits and pieces others so carelessly discard.

7. Bantar Gebang, Jakarta, Indonesia

Pickers fill baskets with the items they salvage. Photo: Mark Tipple

There are cafés, a small outdoor cinema, and even temporary volleyball courts. The trash mountain of Bantar Gebang is practically a town of its own, with around 2,000 resident families, and more people arriving all the time. Materials for the houses and shacks are scavenged from the dump itself: discarded wood, carpet, furniture - no material or object goes to waste in this sprawling, 110-hectare (272-acre) refuse heap.

Fellow trash sorters share a lighter moment. Photo: Mark Tipple

The amount of trash that passes through the Bantar Gebang Waste Landfill (as it is officially known) in Bekasi, East Jakarta exceeds a staggering 6,000 tons every day. It’s enough to sustain the thousands who live and work here in Indonesia’s largest garbage dump, removing cans, rags, plastics, glass bottles - anything they can sell to recycling companies - from the unsorted waste. Even meat and vegetables that have been thrown away get cooked and eaten.

Working in the shadow of heavy machinery. Photo: Mark Tipple

In spite of social stigmas, men like ex-rice farmers are drawn to Bantar Gebang because of what they can earn - about 30,000 rupiah ($3.20) a day. Some of the scavengers are children who labour alongside their parents from as young as five years of age. The money these children make helps to support their families, so their mothers and fathers appreciate them working as an extra pair of hands.

Collecting to survive. Photo: Mark Tipple

Yet steps are being taken to improve the lot of those in Bantar Gebang’s community. The International Labour Organisation is working with an elementary school to widen the options of the children who pick through trash at the dump. Meanwhile, a local hospital provides the scavengers with free healthcare, which is critical when their livelihood puts them at risk of so many illnesses - from skin diseases and nutritional deficiencies to tapeworm and TB.

Those who labour here have little in the way of protective clothing. Photo: Mark Tipple

There is even a newly opened initiative that generates power from methane produced by the dump, with the gas trapped using pits and converted into energy. It is hoped that the dump will eventually be able to create more jobs and better working conditions for the people in the area.

6. Smokey Mountain, Manila, Philippines

A garbage truck at the appropriately named Smokey Mountain. Photo: Janssen and De Kievith Fotografie/Philippines Photography

There are no steps up the 20-meter (65-ft) slope of Smokey Mountain; only a rope so people can pull themselves up the steep sides to the top. This is central Manila’s famous, 50-year-old mound of decomposing trash, so-called because of the fires that burn here. While it was officially closed in 1995, it is estimated that as many as 30,000 people continue to live on and around the dumpsite, many inhabiting shacks built out of scavenged materials and getting by collecting recyclables like plastic bottles, scrap metal, paper, and wood burned for charcoal.

A young girl with her collection basket. Photo: Janssen and De Kievith Fotografie/Philippines Photography

When the government decided to shut down Smokey Mountain, they bulldozed the homes of thousands of people who scavenged materials at the site. And while housing built by the garbage dump was designed to accommodate the former trash pickers, in the absence of other sources of income, many were forced to move to other dumpsites like Payatas (see entry 1) and scavenge there instead.

Life in Smokey Mountain. Photo: Janssen and De Kievith Fotografie/Philippines Photography

Life was undoubtedly harsh for the men and women who sorted through Smokey Mountain’s trash - diseases such as cholera and TB, for example, were present in the 1980s - yet the closing of the dump actually lowered their living standards. However, since the site is officially closed, the government feels less pressure to act on the problems of those who remain in the area’s slums.

Even the very young are roped in to work here. Photo: Janssen and De Kievith Fotografie/Philippines Photography

Nevertheless, there are non-governmental agencies working with the waste recyclers to offer them better futures in Smokey Mountain. Charities like Gawad Kalinga, for instance, help impoverished residents through various projects: one involves Smokey Mountain’s women creating items to sell out of recycled clothes; others entail providing residents with healthcare or after-school care for their children.

Children congregate on the garbage heap. Photo: Janssen and De Kievith Fotografie/Philippines Photography

Ultimately, however, there is still a long way to go before a solution is found to the issues of both garbage disposal and poverty in Smokey Mountain and other similar places around the Philippines.

5. Jardim Gramacho, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Night-time fires. Photo: Ben Lievens

In early June 2012, the largest dump in Latin America - and one of the biggest in the world - shut down for environmental reasons. The Jardim Gramacho landfill in Rio de Janeiro was the dumping ground for around 60 million tons of waste during the 34 years it was operational. At its time of closing, it is said to have supported as many as 5,000 scavengers, who collected and sold the recyclables from the 50-meter (165-ft) tall, 130-hectare (321-acre) trash heap.

A man takes a break in Gramacho. Photo: Bens Lievens

Before it was closed to stop the seepage of toxic fluids into the sea, the garbage pickers (known as “catadores”) in Jardim Gramacho led a difficult and perilous existence. Alongside vultures and pigs, and amidst rancid smells, they toiled for over ten hours every day in blazing heat - or indeed, any weather - and regularly suffered health problems from contact with the untreated trash. Yet despite this, and the social stigma of their work, there was a great community spirit among those who sorted through the discarded produce, and a dignity about their labour.

All kinds of junk can be recycled. Photo: Ben Lievens

Gloria Cristina dos Santos recycled garbage at Gramacho for 25 years, and now she represents a cooperative that aims to train the scavengers and get them better living and working conditions. “Working in Gramacho was never disgraceful, but it was always inhuman,” she says. “I’m not ashamed to be a recycler; it’s a way to support my family. Now we will remain in the recycling supply chain in a more organized and safer manner.”

4. Dharavi, Mumbai, India

Treasure among the trash. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica

Unlike most of the other grassroots recyclers described in this article, the residents of Dharavi live not on a single garbage dump but in one of Asia’s largest slums - spread over an area of 175 hectares (432 acres). Yet the word ‘slum’ is perhaps somewhat misleading here, as although Dharavi lacks infrastructure such as roads and adequate sanitation, it can also be viewed as an inner-city township, and one that contains various thriving industries - not least, recycling.

Two women sit on a pile of bottles for recycling. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica

Dharavi’s recyclers work their way through upwards of 4,000 tons of waste every single day. They process everything from paper and glass to aluminium and plastics in an industry that employs around a fifth of the area’s estimated 1.2 million inhabitants. Children and adults toil here all day long, sorting through, breaking up and reassembling anything of value in Mumbai’s municipal waste.

Materials being melted down for re-use. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica

“Not only does recycling provide nearly 25 times more jobs than landfill or incineration, it also offers far greater economic, social and environmental benefits,” says Laxmi Narayan, the general secretary of a waste picker trade union. “If they stopped doing what they do, the city would be swimming in filth,” adds Vinod Shetty, the director of an initiative aimed at helping those living in Dharavi.

Empty tins for recycling. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica

Yet although there are positives about the environmental service the recyclers provide, their working conditions in Dharavi often leave a lot to be desired. Despite the skill their work entails, many of them slog away in small, inadequately equipped factories and receive little profit from what they do.

Boys recycling trash in Dharavi. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica

The waste pickers are not only marginalized and invisible: disease, injury and pollutants are daily risks. One study suggests that working with unsafe garbage can lead to a 40% reduction in people’s life expectancy in the developing world. For such reasons, there are various groups working in Dharavi to improve the lot of the trash pickers, by helping them get access to training, education and insurance. Yet, while progress has been made, much still needs to be done - making provisions for tools and protective clothing, for instance.

3. Ulingan, Manila, Philippines

Smoke fills the air in the Ulingan section of Hapilan. Photo: Jimmy A. Domingo

The air is hot and thick with noxious smoke in the Ulingan community of Manila’s Tondo district. Here, in filthy conditions, people survive by scavenging re-sellable items and materials - but also, more specifically, wood that they burn to produce charcoal. Much of the timber is salvaged from garbage dumps and demolished construction sites, but these resourceful charcoal makers need a lot of it: 4.5 tons of dried wood results in only about a single ton of charcoal.

Whole families are forced to work here for survival. Photo: Jimmy A. Domingo

Making charcoal is an industry that involves whole families, including even very young children. Working around fire pits without gloves or masks - and breathing in toxic fumes such as carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide - family members make sticks and ‘doughnuts’ of charcoal, while the young rake through the ashes looking for scraps of metal like nails that they can sell as scrap. Understandably, respiratory illnesses, heart diseases and skin conditions are rife.

Sometimes, surprising things can be salvaged from the trash. Photo: Jimmy A. Domingo

Although the government does not encourage the activities of the charcoal makers of Ulingan, for many it is a matter of survival. And the folk here are trying to better their lives by saving money, with some funds having been used to pave some land near where they live and also to set up a day care centre.

Additionally, a non-profit organization is paying for many of the children of Ulingan to attend school and also provides meals for the young and elderly. Founder Melissa Villa says the organization’s ultimate goal is to “eradicate child labour in Ulingan.” A bold ambition, but certainly something worth aiming for. Until then, the people of Ulingan will persevere, earning an honest living under incredibly harsh conditions in a manner that demands more than a modicum of respect.

2. Mazatlán Garbage Dump, Mexico

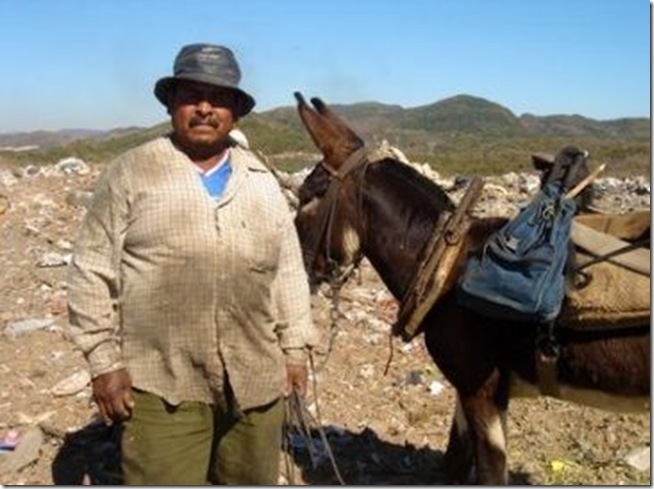

Sorting through the garbage. Photo: Ruah Edelstein

It looks like some kind of mountainous landscape, except the prominence here is not made of rock and soil but of the refuse created by the Mexican city of Mazatlán’s population. On the foul-smelling slopes, men and women sort through the compacted trash, picking out anything of value they can sell - be it scrap metal, plastic and paper, or clothing and food - and all under a canopy of birds that circle the giant garbage pile looking for scraps of their own.

A trash recycler in Mazatlán. Photo: Ruah Edelstein

The people in Mazatlán’s garbage dump live either on or just outside the site itself. The homes on the dumpsite are themselves made of recycled materials - everything from cardboard to shipping crates. It is a community many of whose members know one another, and it is built on a system of respect. The shacks are not blocked or fenced off, and the trash pickers leave their piles of salvaged items all over the dump with little fear that they will be touched by anyone else.

These days, there are organized tours of the dumpsite, as there are of other slums like it around the world, and just as in other parts of the globe, the tours in Mazatlán are controversial. Even so, there is a sense of pride in the work these uneducated and out-of-work grassroots recyclers do. As Santiago, a garbage truck driver, says, “They help us clean the city, they help the environment. None of this would be recycled or used again if they weren’t here to do this.”

1. Payatas, Quezon City, Philippines

Young boys in Payatas. Photo: Rudi Roels

In July 2000, torrential rains in the Philippines caused an enormous landslide of waste that plunged from the 30-meter (100-ft) high Payatas garbage pile on Quezon City’s northern edge. At least 200 people died - buried beneath the mass of trash in which they scavenged and in whose shadow they lived. The tragedy alerted the world to the conditions the rag pickers and dumpsite residents faced here (and in other developing countries worldwide) and the perilously steep face of the dumpsite was thankfully made more stable.

A man sorts his trash collection. Photo: Rudi Roels

As recently as 2006, at any one time the towering 20-hectare (50-acre) Payatas dumpsite swarmed with hundreds of people scouring the surface of the giant pile of debris and digging through the trash with special steel spikes. The scavengers would take anything sellable - from plastic cups and straws to scrap metal - working with amazing efficiency amidst the smell of rotting and burning refuse. This was daily life for these “mangangalahigs” (loosely, “chicken-scratchers”), many of whom come from rural areas where farming work offers far less money.

A woman sits amidst garbage in Payatas. Photo: Rudi Roels

The dignity and organization of the trash pickers was evident in initiatives such as collectives in which scavenging profits were shared and in ‘food courts’ where they could eat for a few pesos. Different trash pickers also have different ways in which they work; some on the garbage trucks themselves, others on the newest piles of trash. Of course, threats in such environments lurk everywhere: for every valuable find - gold, money, watches - there is a hazard to be faced. And if it isn’t something tangible, then there’s always the spectre of disease: TB is rife, and tetanus, asthma and other infections are all too common.

A truck surrounded by workers. Photo: Rudi Roels

Over recent years, Payatas became more tightly regulated, with security guards overseeing the arrival of the rumbling garbage trucks and the subsequent sorting of the waste by the scavengers. The dumpsite even supports families, who sell reusable items from the trash pile to junk dealers.

The government also has big plans for the site. A methane power plant is planned that could convert the millions of tons of refuse into electricity - enough to serve the needs of around 2,000 nearby homes for ten years. Meanwhile, tires recovered from the site are being used to fuel cement production.

View out onto green space from Payatas. Photo: Rudi Roels

According to the local authorities, many of the people who scavenge from the dump now have their sorting and recycling tasks formally organized. Of course, whether all this will happen as planned, and the displaced rag pickers do not simply move to other sites where conditions are worse, remains to be seen.

People gather around a garbage truck in Jardim Gramacho, Rio de Janeiro, ready to sort its contents.

Photo: Ben Lievens

Nowadays, many of the world's large, open dump sites seem to be being closed down, often for environmental reasons. It’s only hoped that the thousands of people who have subsisted on the recyclable materials collected in these places can find other work and better lives. Surely any industry would be lucky to have such resilient, hard-working and skilled employees as these grassroots recyclers.

Top image: A man wades through water surrounded by trash in Dharavi, Mumbai, India. Photo: Pierpaolo Mittica.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.