The airliner is one of the pinnacles of the modern era: beautifully engineered, high-tech, bewilderingly complex, but accessible by all. Billions of people have travelled at blistering speeds at unimaginable altitudes to every corner of the world, often without a second thought for the enormous amount of technology and engineering all around them. Air travel arguably has done more to unite the globe than any other invention known to man. We live in the jet age.

But there are some things even frequent flyers have never realized about the aircraft they travel in, small peculiarities about the modern airliner that live outside the realm of most people’s common knowledge. Until now, that is.

10. There Are Explosive Charges Inside The Engines

Let’s ignore the fact that the entire wing is filled with dangerous and highly flammable fuel for a second (yes, that’s where the fuel goes). Each engine also comes fully equipped with one (sometimes two) explosive charges, which are known as “squibs.” Surprisingly, these are used to combat engine fires. Upon firing, the explosive charge punctures the airtight seal of a highly pressurized bottle, and a fire-retardant chemical is violently expelled all over the engine’s interior to – hopefully - smother any flames that remain in the engine casing.

Most aircraft come equipped with two charges - the idea is that firing one should do the trick, but if that fails the second should buy the aircraft a few more precious seconds while it finds somewhere nearby to land. The fire suppression systems in aircraft cargo bays work under similar principles. It’s comforting, in a rather bizarre way.

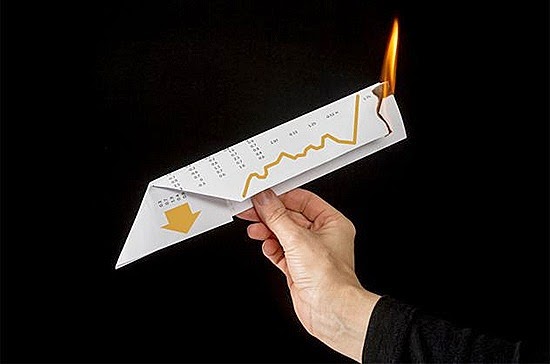

9. Your Aircraft Might Be More Broken Than You Think

Every company wants its planes to fly, as often as they can, with as full a load as they can. If an aircraft isn’t in the sky, it doesn’t earn any money. So when part of the aircraft breaks, there is tremendous pressure on the part of the airline to get the flight underway again as soon as possible. But full-blown repair jobs can take hours, potentially even days, and there are times when a breakage could be seen as trivial, such as a malfunctioning coffee pot or a broken light bulb. So what decides whether a broken component means an aircraft can’t fly?

The answer is a document known as the MEL, or Minimum Equipment List. Any failure is looked up in this list, and it will let you know whether you need it for a particular flight; it also outlines any procedures the pilots must apply to cope with its loss. What this system permits, however, are aircraft flying around in the sky that are potentially operating with only half the usual systems. It’s still safe, of course - unless that other half also decides to fail, and then the redundancy is gone. Ultimately, it’s up to the captain of the flight to decide whether or not to take the aircraft in its current state, but the company can always swap to another captain who would be willing to accept it.

In the middle of a busy summer season, when an airline cannot afford to fix something but can instead continually defer its repair (up to a point), there is little incentive to properly maintain the aircraft until the end of the season, which means that many aircraft in service today are defective in some way or other.

8. The Cabin Air Comes From The Engines, Not The Outside

Cabin air is not the same as the air outside the aircraft. At the altitudes that commercial airliners fly at, the air has the same composition (still 20 percent oxygen), but it’s far too thin for a person to breathe and also hope to remain conscious. The solution that engineers came up with was to take air from the engines, engines that already compress the air for their own use, so that there is a supply of denser, usable air for the passengers to breathe. It still won’t be the equivalent of the air on the ground, of course - that would make too much of a difference in pressure between the inside and the outside of the cabin - so most aircraft look for a happy medium. The air you’re breathing is basically what you’d find at an altitude of 2,400 kilometres (8,000 ft).

The downside to this system is, of course, that anything that goes through the engine is also likely to end up in the cabin, such as noxious smoke if the engine catches fire, fumes from de-icing fluid, or, as has been increasingly reported, toxic compounds from the burning of lubricating oils within the engine itself.

7. Emergency Decompression Is A Lot Worse Than You Think

When the cabin crew inform you to “put your own mask on before helping others,” they are not kidding. The air at high altitude is so thin that, in the event of a full decompression, your lungs would only be able to supply your brain with enough oxygen to keep you awake for approximately 30–45 seconds, depending on your physical state and the aircraft’s actual altitude. During that time, you would feel increasingly euphoric, then dizzy, and then finally you’d be unable to form decisions before lapsing into unconsciousness. While one minute might seem like a long time, the side effects of lack of oxygen to the brain (hypoxia) make it all the more important for you to get supplementary oxygen as soon as possible.

To make matters worse, air at high altitudes is cold - very cold. Temperatures of around -60 degrees Celsius (-76 °F) are not uncommon. And circumstances around such a decompression are likely to involve lots of rushing air, cabin detritus billowing about, and, in most cases, visible fog, all of which are likely to send passengers into shock. If anything like this is unfortunate enough to happen to you, be sure to follow the emergency advice and get your own mask on first.

6. Oxygen Masks Don’t Last Long Either

The small, yellow masks that supply you with oxygen do just that, but not in the way most people think. While you’d imagine that you would be breathing in cool, pure oxygen, like from a scuba tank or hospital machine, the reality is anything but. Each set of four or five masks is linked to a chemical generator, a lump of metal which is ignited by pulling any one of the masks down. The burning of that metal produces more oxygen than the fire needs to self-sustain, and that extra oxygen is what you breathe. It will be hot, smoky, and have an unpleasant smell and taste.

Of course, the metal can’t burn forever, and will run out after around 12 minutes, which should give the pilots enough time to manoeuvre the aircraft down to a breathable altitude. To top it all off, the small, flimsy mask is not filtered or sealed, meaning that it won’t protect you from any fumes or smoke already in the cabin. But hey, every little bit helps, right? And not to worry - your pilots’ oxygen is bottled, and lasts for around two hours.

5. Escape Slides Don’t Always Double As Life Rafts

It’s common to assume that if your airliner crashed in the ocean, you’d be able to float high and dry inside the escape slides. But next time you get on board an aircraft, take a close look at that emergency card. If the figures representing passengers on the card are depicted floating next to the slide with one arm over the side and not sitting in it, your emergency slide will just tip over in the water if anyone tries to climb aboard. That’s because the majority of aircraft in use over land are only required by law to be equipped with slides that make it easier to get off in a hurry on dry land.

The thinking behind this is that raft slides are heavier than non-raft slides, and it’s unnecessarily inefficient for aircraft that routinely fly close to land to carry that much extra weight. Even if the aircraft crashes near the coastline, you’re still closer to rescue than you would be in the open sea. Fortunately, there are no incidents of raftless aircraft having to crash-land in water.

4. Your Aircraft Was Certified Safe...Through Bribery

After a high-profile engine fire on the ground in Manchester, UK caused a previously unimaginable loss of life, safety officers and researchers looked to recreate emergency evacuations on the ground in an attempt to understand why so many people unnecessarily died. However, they soon hit a brick wall - in all their simulated evacuations, the passengers were so calm and polite to each other that every evacuation ran smoothly, a far cry from the panicked, chaotic survival mentality that would envelop each passenger in a real emergency.

So how did the researchers evoke that feeling of desperation? Easy: They promised a monetary reward to the first few people off. And they found that they needed to offer no more than £20 to turn the average person into the pushing, scratching, clambering-over-the-seat-backs desperate evacuee that they had been looking to simulate. Thus, the researchers had their data, and aircraft certification has been done much the same since.

3. Portable Electronic Devices Have No Effect On The Aircraft’s Systems

This is common sense and is finally being accepted around the world as aviation authorities relent and permit passengers the use of PEDs (personal electronic devices) during most phases of flight. In some circumstances (such as poor visibility, low clouds, fog, etc.), aircraft use precise radio signals beamed from the ground to help them navigate through the final phases of flight, and the theory was that devices such as mobile phones would interrupt these signals and cause the aircraft to swerve dangerously off course. Such radio signals are already sensitive, and whenever they are being used for low-visibility manoeuvres, other aircraft are kept much farther away from the runways so they don’t disrupt the signal.

So surely the fear of interference from other devices like mobile phones was justified, right? No evidence of this interference has ever been found, and the likelihood was always absolutely minimal. What manufacturer would design a multi-million-dollar aircraft that could be brought down by a US$10 mobile phone? As an excellent radio comedy series put it, “If they had any effect we wouldn’t let you have them.”

2. ...But The Pilots’ Mobile Devices Have Caused Incidents

That’s not to say that mobile phones have never caused incidents with potentially fatal consequences. As an aircraft is descending toward an airport, the closer it gets to the ground, the more safety-critical its flight path becomes. Unfortunately for a few pilots, getting closer to the ground also makes it more likely that one of the pilot’s mobile phones will receive a signal and start to vibrate, beep, or make otherwise very distracting noises at a critical moment.

In one incident, the pilot’s phone caused him to forget to lower the landing gear of a Jetstar A320 as the aircraft was coming in to land. Another potential danger is on take-off - in 2009, the FAA reported that an airliner almost abandoned its take-off at the last minute (a dangerous manoeuvre) because of an unknown “warbling” from the First Officer’s mobile phone.

1. “Minimal Fuel” Isn’t As Bad As You Think

Airlines such as Ryanair and Easyjet are lambasted these days for carrying around “minimal fuel,” as if they are barely making it to their destinations and landing on fumes alone. The news passengers probably don’t want to hear is that the overwhelming majority of modern airlines use this practice for the sole reason that if you carry more fuel than you need, you actually burn more fuel just to move it from A to B (more weight means more work for the engines).

The good news for passengers, though, is that “minimal” does not mean just the fuel required to travel between your departure airport and your destination. Under international aviation law, all aircraft are required to carry the trip fuel (fuel for your actual trip), a certain amount of spare fuel (“contingency fuel,” which would cover between three and five percent of the trip), and then a further amount of fuel to be used in case of diversion (“alternate fuel,” or enough fuel to go from B to C if you arrive at B and it’s closed). They also carry a final reserve of fuel, equivalent to half an hour of flight.

So if everything goes to plan, you will only ever burn the “trip” fuel, with enough to spare for at least another 30 minutes of flying. If an aircraft lands with less than the “final reserve” in its tanks, both the crew and airline will automatically be investigated. And finally, it should always be made absolutely clear that very statistic we have confirms that flying is the safest form of transport known to man.

Enjoy your flight!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.