10 of the Most Remote Places on Earth Where People Actually Live

By Debra Kelly, Urban Ghosts Media, 20 November 2014.

By Debra Kelly, Urban Ghosts Media, 20 November 2014.

In a time that many of us take internet access, a mobile phone signal and cable TV for granted, it’s easy to forget that there’s still a number of remote corners in the world where people still have limited comforts like electricity. For some, the problems of daily life are still more closely related to survival than to comforts.

10. Kake, Alaska

Image: Umnak

Kake, Alaska is a small community about 114 miles from Juneau, the state capital. It might not sound like too far, but out in the desolate Alaskan wilderness, the only way to get to or from Kake is by air or by boat. It’s home to a little over 650 Tlingit people; known for their strong connection to the earth and the land, the Tlingit people are spread throughout Alaska, down the Canadian coast and as far south as Oregon.

Getting there requires booking a chartered plane, taking an air taxi, or getting on Alaska’s Marine Highway System. There’s two trips between Kake and the mainland every week - one going north, one going south. There’s no ferry terminal building, either; just a shed at the loading points.

There’s car rentals on Kake, along with kayak rentals and a few lodges to stay at, but banking is non-existent in the small fishing village.

Image: Umnak

The remoteness of Kake makes it something of a dangerous place. The town recently made the news with the murder of a 13-year-old girl; with no roads for the state troopers that are the area’s only law enforcement, a group of citizens were appointed to stand watch over her body overnight until state troopers could get to the town. Rural Alaska is almost as crime-ridden as it is breathtakingly beautiful - in other remote areas like Kake, physical assaults are at a staggering 12 times the national average, while domestic violence is 10 times the national average. Kake is just one of about 75 small villages with similar problems - they’re remote, they can’t support their own law enforcement, and most of them don’t even have roads leading to them. Emergency response time is about a day and a half in many of the areas, leaving those who live there to fend for themselves.

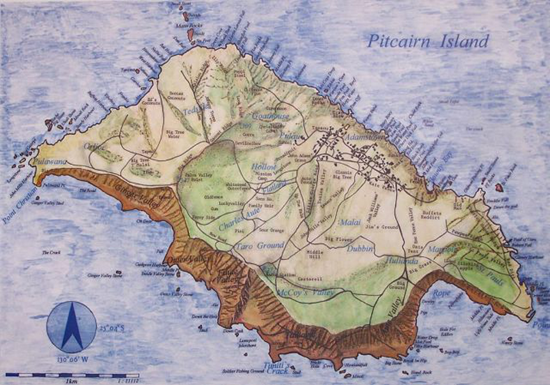

9. Pitcairn Island, South Pacific

The tiny island in the South Pacific is now home to about 50 residents, and the British Overseas Territory is looking for immigrants to help rebuild the native population. It’s a tough sell, though, with the island only accessible by sea and a supply ship only visiting once every three months or so. Until 2002, the only communication the island had with the outside world was by HAM radio. They do, however, have rich, fertile land, a largely pollution-free island, breathtakingly beautiful beaches, a rich marine life, and a fascinating history.

In 1790, Pitcairn Island was settled by the mutineers from the HMS Bounty. Led by Fletcher Christian, the island’s European settlers stripped what they could from their ship before setting it on fire - making sure that no one would see the ship there and that no one would find them. Christian himself died after only a few years on the island, but today, most of the island’s residents are made up of the descendants of the original mutineers and the 18 Polynesian settlers they brought with them from Tahiti.

Their settlement might have continued to go unnoticed for a long time, if not for its accidental discovery by an American whaling ship in in 1808. No one would return for years, and in 1814 two British ships made their way to the island to discover not only the settlement, but what had happened to the HMS Bounty.

Today, the island has its own holidays and traditions, and much of the islanders’ daily life revolves around fishing, diving, and gardening.

8. Ittoqqortoormiit, Greenland

Greenland itself is pretty remote, and the oddly-named Ittoqqortoormiit is the remotest town there. Nestled deep in the world’s largest fjord system, the town is shut off from the rest of the world for about nine months out of the year - that’s how long the ice in the ocean around it is frozen for. Founded in 1925, it’s currently home to about 450 people who rely on hunting and fishing to survive.

Whatever they lack in conveniences, they more than make up for in sheer breathtaking beauty. There’s only one grocery store in the town, but they’re just a stone’s throw from the largest National Park in the world and the tallest of all the Arctic mountains - Gunnbjorn. Nearby are a handful of uninhabited settlements, including one that was built near the hottest hot spring in Greenland - the 620 Celsius (1,148 Fahrenheit) Uunartoq. In recent years, the townsfolk have added another source of income to their lifestyle - tourism.

The adventurous can rent kayaks and dog sleds, go hiking, get up close and personal with arctic wildlife, and get a front-row seat for the Northern Lights.

7. Supai, Arizona

The mainland United States might be the last place you’d expect to find remote, isolated villages, but the Native American village of Supai absolutely qualifies. It sits in the middle of the Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona, and like many of these remote places, it’s absolutely breathtaking.

The village is the home of the Havasupai, which means ‘People of the Blue-green Waters’. Sitting in the Havasu Canyon and on one of the largest tributaries of the Colorado River, the village is surrounded by countless waterfalls, stunning rivers, travertine pools, blue skies, and bright, colourful rock formations that can only be found in the deserts of the American Southwest.

Supai village can only be reached by taking on the 8-mile hike down the canyon, or by renting mules that are commonly used to carry people and supplies back and forth to the village. It’s also accessible by helicopter, with some stunning views of the surrounding canyon. It’s also home to the only U.S. Mail Mule Train left in the country, and unlike some of the other remote locations here, it’s regularly visited by tourists - about 20,000 visitors every year come from around the world to camp and hike in the Arizona sun. The town itself remains small, though; it’s home to only a 25-room lodge and a single restaurant, with most tourists opting to stay in less remote, more accessible nearby areas. That also means that those who visit the village need to be prepared to carry in and out what they need for their stay - that includes camping gear, clothes, food and plenty of water for the long, hot hike.

Because of the village’s position in the canyon and near the sometimes unpredictable Colorado River, it’s also prone to flash floods. It’s worth the risk, though, to see breathtaking sights like Havasu Falls and the 200-foot Mooney Falls.

6. The Aucanquilcha Volcano, Chile

The 6,176-meter summit was occupied up until the 1990s. Aucanquilcha was the site of the highest permanent human settlement from 1913, a small village of miners that was located just below a working sulphur mine. The mine was ultimately abandoned in 1993; much of the man-made roads up into the mountains has been destroyed by landslides.

In theory, it would be easy enough to drive up the road into the mountain. The volcano, which is subject to regular tremors and erupted less than 10,000 years ago, was the site of the highest navigable road in the world. When the settlement was first established, however, the lack of oxygen at that altitude meant that it was necessary to replace machinery with animals such as llamas and technology that relied less on engines and more on systems like pulleys and ropes.

The settlement is on the side of what is the largest and youngest of the volcanoes in the region; it’s still regularly monitored for activity, and the remains of the mining camp is still there.

The area is also vulnerable to unpredictable storms and fierce winds, which makes already tough terrain even tougher. At that altitude, the human body is forced to adjust itself to low oxygen levels, a process that can take days. Usually that means chronic shortness of breath, and can also mean swelling in the extremities and trouble sleeping - which may or may not disappear once a person gets used to the altitude.

5. Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha has the title of being the world’s remotest inhabited island. It’s home to around 270 people, who are all farmers and who all live in the 8-mile long, 38-square-mile island’s single settlement, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas.

The island is a British Overseas Territory, and with such a small community, they’ve taken the opportunity to put in place some amazing rules. All the land is communal land, and families work together to ensure that everyone not only works and does their fair share, but shares in the profits as well. The island has one road, electricity supplied by generators, and orders must be placed with the island’s only grocery store months in advance. Since there’s no airport, the only way to get to the island is by boat - and the trip takes seven days from Cape Town, South Africa.

The island was first discovered in 1506 by the Portuguese sailor it’s named for. It’s 1,750 miles from South Africa, and 2,088 miles from South America - it’s only recently been given a post code, because mail directed to those in its capital city was going to Edinburgh, Scotland instead. The island gets an average of 20 rainy days every month and sits on an active volcano that last erupted in 1961, but has such a beloved way of life that nearly all of those that were evacuated during the last eruption returned as soon as they got the approval to do so.

4. Krasnoyarsk’s Villages

The city of Krasnoyarsk itself is one of the biggest and most populated of Siberia, but there are a number of small villages in the outlying areas of the regions that are so remote, they’re home to only a few individuals. The region, known for its bitterly cold winters and scorching summers, has another odd problem associated with its remote villages - they’re mostly male-only.

The small, remote villages are so far off the beaten path that their male-dominated nature wasn’t even realized until 2013. The region as a whole has nearly 200,000 more women than men, but that’s not counting the most desolate of villages.

Lokatui, Kasovo, and Novy Lokatui have one resident each, and Illinka is only slightly bigger, with three men living there. Still more have only four or five people there, but those that do live in these remotest parts of Siberia live a long, long time. The entire region has more than 70 people over the age of 100.

3. Lajamanu, Australia

There are vast expanses of the Australian Outback that are largely uninhabited, unexplored, and undeveloped. Scattered across these expanses are countless small villages of aboriginal natives and recently, a startling new phenomenon was discovered in the remote Lajamanu.

Home to about 700 people, Lajamanu is about 340 miles from the nearest commercial centre. There’s no real paved roads between Katherine (below) and Lajamanu, forcing anyone who wants to get there to make a pretty hazardous overland journey across the untamed Outback. Once a week, a truck brings food to the town’s single store, and the only electricity comes from a few solar panels and a single generator. The village itself has a rather tragic history. It was formed in 1948 by the Australian government, in an attempt to settle people well outside of areas that were becoming overwhelmingly crowded. The original inhabitants weren’t volunteers, either - they were forcefully relocated to the fledgling village, out in the middle of nowhere. Those who tried to return to civilization were taken back.

It wasn’t until 1970 that the village settled into something resembling a normal community. And in 2013, the settlement gained the attention of university linguists for the language that was being born there.

While seeing a language die out isn’t too incredibly uncommon, seeing one develop is another matter. The children of Lajamanu began speaking an entirely new language, with new dialects and new rules. It was started when adults spoke to their children in a combination of their native tongue - Warlpiri rampaku - and English, along with a couple of other languages thrown in. Linguists have been fascinated by the development of this new language, as they’ve managed to distinguish it from simply being a creole language, or combination of rules and words from other forms of communication. The new language is spoken only by those under the age of 35 in the community, and its development is a phenomenon linguists attribute to the remoteness of their village.

2. Bakhtia, Siberia

Image: Music Box Films via Slate

There’s about 300 people living in this Siberian village at any time, and it gives new meaning to the word “remote”. There’s no running water, no telephone, no immediate access to hospitals or other medical help. The entire area is covered with ice and snow that only retreats for a few months out of the year - for the rest of the year, the temperature is well below freezing. The only way to get there is by boat or by helicopter, and that’s when the weather’s right.

The families that live in the sub-zero temperatures of the Siberia Taiga were the subject of a 2013 documentary called Happy People: A Year in the Taiga. The footage, captured by a filmmaker who spent a year living in the remote village, shows a lifestyle that hasn’t changed much in the last few hundred years. They have an undeniably close relationship with the land, rely on their dogs for hunting, companionship and survival, and make a living trapping, fishing, and growing root vegetables. Today, they have access to modern amenities like chainsaws and snowmobiles, but aside from that, their lifestyles - and certainly their values - might look more familiar to our Iron Age ancestors than they do to us.

It’s a lifestyle that looks absolutely foreign, where lengthening nights and temperatures getting colder means that the biggest worry has become survival. It’s an unnerving concept in a world where much of Western society is preoccupied with setting the DVR and what to make for dinner. In Bakhtia, they spend their summers stockpiling enough supplies to get them through the long, endless days of winter darkness.

1. Palmerston, Cook Islands

Image: via BBC

It’s been called the Island at the End of the Earth.

Palmerston in the Cook Islands is visited by a single supply ship twice a year, if those that live there are fortunate. It’s home to about 60 people, and all of those people are descended from its original inhabitant, William Marsters. Marsters settled on the island in 1863; he left his first wife and their two children in England, took up with three Polynesian women, and made Palmerston home. By the time he died in 1899, he had 17 children and 54 grandchildren. Now, his descendants are in the thousands, but only a handful have stayed on the remote island paradise.

There are 2 telephones on the island, and internet access - for four hours each day. There’s only power and electricity provided for a couple hours a day, too. Its position was only accurately described on maps in 1969, and even today a journey there - by boat - can take days and mean braving ocean storms along the way.

Palmerston is one of several islands connected by a coral reef that has spelled disaster for countless ships. Officially territory of New Zealand, the native families take turns catering to the needs of the handful of visitors that are brave enough to make it to the island every year - and they pride themselves on their generosity and hospitality. Money is only needed when they’re dealing with the outside world, as the communities share amongst each other for everything else - and that includes taking advantage of the coconut trees that Marsters originally planted across the island for coconut oil - once his only export.

Main Street is a strip of sand.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.