Cybercrime: 10 Ways Criminals Use the Internet for Organised Crime

By Debra Kelly, Urban Ghosts Media, 23 November 2015.

By Debra Kelly, Urban Ghosts Media, 23 November 2015.

The internet and especially social media have had an unprecedented impact on almost all areas of life. From how we get directions to how we shop, our everyday lives have become dependent on the internet. But at the same time as we’re doing our holiday shopping or looking at cat pictures, it’s easy to overlook just how dark some corners of the online realm can be. Organized crime has set up shop there, too, and their influence over social media and the web is as bizarre as it is sinister.

1. Hitmen for Hire

According to InSight Crime, it’s alarmingly simple to hire a hitman on Facebook. A Peruvian newspaper called El Comercio wanted to find out just how accessible the likes of assassins and hitmen were, so they contacted a Facebook group called Los Pulpos. The reporter asked about hiring a contract killer, and was told it wasn’t a problem - speed and efficiency guaranteed, for the shockingly small sum of US$110.

The newspaper Peru 21 reported that Los Pulpos (now shut down by Facebook) was not the only group using social media to match clients with hitmen, with at least three Trujillo-based gangs having set up on Facebook. Members have reportedly bragged about how well their previous jobs went. Some even posted their phone numbers on the page, supposedly allowing anyone interested in hiring the assassin to arrange a hit.

It was also reported that platforms like Facebook had been used to spread propaganda and recruit new gang members. Law enforcement has estimated that some gangs have increased their membership by around 40 percent in six months, recruiting from social media-savvy teens. They also report that such sites are easily accessible for anyone who wants to get their foot in the door, with numerous posts from people asking for training in weapons and in how to be a hitman.

InSight Crime also points out that those who are tech-savvy enough to post on Facebook for clients are also using it to target victims and to finish their jobs, due to the ability to access a wealth of information that people tend to post online without a second thought.

2. Money Laundering in Online Games

In 2009, the International Monetary Fund estimated (PDF) that between two and five percent of global GDP was generated by criminal activities, and with that illegal source of income comes the necessity of finding a way to make it appear legit. Online games - specifically MMORPGs - provide an alarming way for criminals to make that happen.

Built into many online games like World of Warcraft and Second Life is the ability to pay real money for in-game, virtual items or currency. Take real, dirty money and purchase those in-game items in a system that, in many games, is unregulated. Then, just turn around and sell them to someone else for real, clean money. Little to no regulations on in-game trading and the relative simplicity of trading across borders have furthered the use of MMORPGs as money laundering engines.

Since there’s no limit to the number of accounts that can be opened in an online game, scammers can open dozens, if not hundreds of accounts for their nefarious purposes. Transferring money from one account to another and then turning it back into cash on the opposite end is often done in relatively small amounts that add up to millions once it finally gets funnelled into the same, real-life bank account.

Some games, like Second Life, have built internal systems to monitor the transactions that go on inside the game in a bid to detect suspicious patterns and activities. But fighting it is no easy feat, with groups including the Russian mob reportedly using online games to move money in and out of the country. Tracing the transactions and identifying them is only part of it, with a nightmare of jurisdictional complications lurking behind every potential case.

3. Crime-as-a-Service Business Model

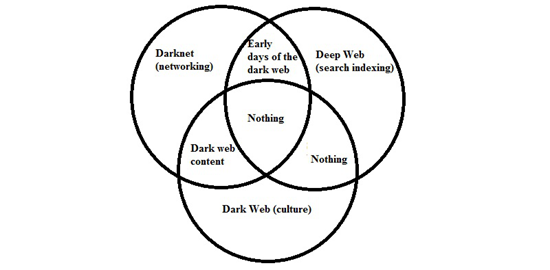

We’ve all heard of the darknet, a deep, shadowy underworld of the internet that’s only accessible through certain channels and protocols. It’s where all the most illegal stuff goes on, stuff that the ordinary person wouldn’t be able to dream up in a million lifetimes. But the goings-on in the darknet are seeping through to the internet realm above in weird ways, and it’s what the Europol Cybercrime Centre (EC3) calls the Crime-as-a-Service business model.

The model is based on the notion that many of the cybercriminals capable of building software to launch a large-scale attack on businesses, corporations and government agencies live in the darknet. There, they not only build the software capable to launching attacks, they also set about selling it to new players in the cybercrime arena. That means that newcomers and initiates into the world of cybercrime suddenly have access to the tools they need to create havoc, which would have previously been well beyond their capability.

This also means there’s a new structure in the world of organized crime, where individual operators meet in the darknet, share software and schemes, and hire themselves out as mercenaries on a job-by-job basis. Factor in the idea of cyptocurrencies and the ease by which they can be transferred across international borders, and organized crime isn’t just something that takes over a city or town any more. According to Europol, bitcoin is quickly emerging as a favourite currency among darknet and internet criminals from drug dealers to human traffickers.

4. RICO and Carder.su

Image: Sean MacEntee

In 2014, the US Justice Department set a precedent in its war against online criminals. RICO, the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, has, according to The Wall Street Journal, traditionally been used against organized crime families. With the use of RICO against a global website Carder.su, its focus broadened to online crime syndicates.

Carder.su was a website allowing anyone anywhere to buy stolen credit card numbers - numbers that were stolen from virtually anywhere in the world. For as low as US$20, buyers could obtain numbers from an organization backed by a complete, international hierarchy of criminal masterminds. According to prosecutors, it was the makeup and scale of the criminal unit that allowed for the use of RICO in the trial.

The defense argued that because they were part of an online network, didn’t know each other in real life and, in many cases, didn’t even know each other’s real names, suspects couldn’t be prosecuted under the RICO guidelines. But prosecutors pointed to a Russian administrator who oversaw the entire organization, sitting at its head dispensing instructions, punishments and rewards like the head of any established crime family.

Even so, it was reportedly difficult to bring down the entire network. Only a handful of people indicted under the charges were actually arrested, with many living well outside the jurisdictional reach of the United States. Nine US residents were taken to trial and one, a 22-year-old man from Arizona, was convicted of buying fake IDs and credit cards, and was reportedly sentenced to 20 years in prison.

5. Online Gambling

Image: Graham Stanley

Gambling has always been something of a hot-button topic, and online gambling has made placing a bet on the big game or fight even easier. But knowing who’s behind those sites isn’t always easy, and there’s a chance that using some online gambling sites may mean supporting some of organized crime’s heavy hitters.

PBS NewsHour used the example of the 2015 fight between Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao. The Las Vegas bout was expected to mean anywhere from US$80 to US$100 million wagered on the event alone, but that’s peanuts by comparison to the full scale of illegal sports betting in the US. In a single year, it’s estimated that around US$800 billion changes hands in the US market alone. Many of those bets are placed through websites, and in many cases, those websites are run out of Asia.

They’re certainly not the only ones involved, though, and according to the FBI agent interviewed in the PBS podcast on organized crime and gambling, the Triads aren’t the only collective involved in reaping the proceeds of online gambling. Agency divisions investigate gambling sites across the world, from Italy to the Middle East, established with minimal risk and maximum rewards. The proceeds from the site are often funnelled right back into the organization’s other illegal activities, meaning that placing a seemingly harmless bet on, say, the World Series might mean dealing with - and funding - organized crime.

These gambling sites, like online games, can also act as money laundering opportunities. A drug dealer in South America, for example, can create an account on a site managed by, say, a syndicate based in Asia. The dealer places a bet with the earnings from his dealings, wins and loses some, and ultimately withdraws his winnings - now safely laundered, and deposits them in another bank account.

6. Ransomware

It’s a basic fact in today’s society: we depend on our computers and our smartphones to keep our daily lives running. From staying in touch with family and friends to booking holidays and setting our morning alarms, losing our connection with technology can present a huge problem for many. Organized crime knows that, which means it’s no longer necessary to kidnap someone in order to demand a ransom. All they need to do is infect and lock our computers, and demand a ransom to get our online world back.

It’s called ransomware, and it usually shows up in the form of an email or is delivered via a website. The attack encrypts your computer with a private key that only the attacker knows, allowing them to demand a ransom for the code. Wired.com reports that a 2012 Symantec survey tracked attackers’ bitcoin addresses used for collecting the ransom. Charging up to US$500 a target, they drew in around US$34,000 a day locking peoples’ computers with ransomware. Since that was based on just two bitcoin addresses, it’s safe to assume the scams are far greater in scope. Symantec estimated conservatively that around US$5 million was generated from ransomware victims annually.

Since then, the scheme has only increased. With the development of CryptoLocker, attackers sought to first infect a computer in a bid to steal bank information, then, as an alternative, to simply lock the computer and demand a payment. The FBI estimates that only about 1.3 percent of victims actually pay the ransom, and that CryptoLocker had earned criminal hackers around US$27 million.

In the meantime, the new CryptoWall has spread things even further, with the lock-out impacting not only a computer but any shared devices too. There’s also something of an affiliate scheme going with CryptoWall, with hackers able to earn a cut of the profits made by anyone they refer to the program.

7. DDoS

DDoS stands for “distributed denial of service”, and according to Business Insider, it’s becoming increasingly popular with American criminal organizations.

In some cases, a DDoS attack can be little more than annoying. In others, though, it can cost victims hundreds of thousands of dollars, and be used to cover up even larger crimes. Attacking is relatively straightforward: a company’s system will be flooded with a massive, unrelenting stream of data, crashing systems across the board. For a major company, that can result in a whole host of problems, from being unable to accept online payments to overwhelming local, brick-and-mortar stores that struggle to deal with angry customers who likely don’t know what’s going on with their service. And now that the software for launching DDoS attacks is more readily available, it’s become a popular tool for organized crime rings that want to cause a distraction.

On December 24, 2012 the San Francisco-based Bank of the West was hit by a huge DDoS attack. While scrambling to stop the attack, which brought down their website by flooding target computers with junk traffic, they were also the victims of a US$900,000 robbery. The set-up was huge, with 62 people conned into unwillingly aiding the movement of money out of compromised accounts. One woman fell victim after uploading her resume to a recruitment site, which allowed attackers to take control of her computer. The bank was left offline for around 24 hours, and by the time they regained control of their website, hundreds of thousands of dollars had been stolen.

Some online criminal organizations are also using the threat of a DDoS attack to extort money, warning victims that unless they pay, their websites will be taken offline for a certain amount of time. PC World stresses that many companies are highly vulnerable to this form of attack. Any group that relies on internet accessibility is a potential victim.

8. DDoS for Information Theft

DDoS attacks aren’t just a way for organized cybercrime syndicates to disguise activities like moving money. They’re also a way to conceal other activities going on within a system. According to Symantec, global cybercrime costs its victims upwards of US$110 billion each year, a number that’s been steadily rising. And cybercriminals aren’t just stealing money outright - sometimes, they’re stealing information.

In August of 2015, Carphone Warehouse was reportedly hit with a DDoS attack. While they were locked out of their system, the personal details of around 2.4 million customers were reportedly stolen. The theft may have included credit card information, but even that’s not the most devastating thing that can be taken.

In 2013, Business Insider reported on an incident detailed only in front of Congress, where one US company lost all the data related to a 10-year, US$1 billion research project. Many of the attacks are understood to have been perpetrated against technology-related firms, and have been traced to cybercrime organizations operating out of China.

9. Silk Road and the Online Black Market

Image: US Government

While most of us might turn to Amazon or eBay as our go-to for ordering just about anything, there’s an entirely darker layer to the internet, where organized crime has moved the sale of all manner of contraband - especially drugs. It started in 2011 with Silk Road, named for the famous trading route of the Han Dynasty. Silk Road is surprisingly similar to eBay - except in what you can buy there.

According to Pursuit Magazine and journalist Kevin Goodman, who infiltrated the cybercrime network, once users got past layers and layers on encryption, they found what was essentially Etsy for narcotics. After creating a user name and password and supplying payment information, buyers could place orders for an astounding array of illegal products. The site held the payment until the buyer confirmed they’d received the product, and, just like other, more well-travelled marketplaces, buyers could rate sellers and provide feedback.

Silk Road reportedly banned the sale of some illegal activities - murder-for-hire, stolen credit card numbers, child porn and weapons. But using bitcoin as the currency of choice, Silk Road quickly became the place to go for practically any drug under the sun. In October of 2013, Forbes reported that the FBI had taken down Silk Road and seized around US$4 million in bitcoins.

According to a Wired.com journalist that interviewed Ulbricht under his online handle - Dread Pirate Roberts - the clause banning certain items was designed to prevent anything sold on the site from being used to hurt third parties. Other black market sites have no such clauses.

Silk Road was, of course, just the tip of the cybercrime iceberg. Wired reports that Evolution, which began in early 2014, had amassed listings detailing around 15,000 illegal products by September of the same year. Evolution didn’t have the restrictions that Silk Road did, either, with about 10 percent of their sales being stolen credit cards and account passwords. Meanwhile, Silk Road was reborn as Silk Road 2, but the criminal marketplace had some stiff competition from newcomer Agora, which surpassed both in product listings, Wired reported.

10. The Online Wildlife Trade

When the International Fund for Animal Welfare began its 2008 investigation into the extent of the wildlife black market, they uncovered a criminal underworld extending far beyond the sale of ivory on underground websites. In 2013, the United Nations Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice went even further, calling the online wildlife trade one of the most serious types of organized crime.

The IFAW (PDF) uncovered an overwhelming number of wildlife-related products available through the same online black markets that were being used for drugs and weapons. From the pelts of the world’s big cats, tortoise shells, shark fins and hunting trophies to bear gall bladders, bushmeat, caviar and pangolin scales, the ease of online sales has skyrocketed the problems facing animals across the world.

In turn, the demand for such products - from people looking to decorate their homes with exotic hunting trophies to those in search of ingredients to traditional medicines - has a domino effect in the regions where these animals are poached. Illegal arms and weapons trade increases, as does corruption, fraud, and even terrorism. The scale is of this form of cybercrime is almost overwhelming. Over the past decade, an increased demand for illegal animal products has caused the deaths of more than 1,000 park rangers across 35 countries.

But it’s not just poaching. The Guardian reported that tools used on the darknet for human trafficking and narcotics have also been deployed for the sale of animals captured illegally. In 2010, the Kaiser’s spotted newt was officially declared at risk of extinction, due to a rapacious black market demand fuelled by those wanting to keep the amphibian as a pet that only about 1,000 individuals remained in the wild. Birds, reptiles and fish are all commonly bought and sold on black market. It’s estimates that the industry nets upwards of £5 billion every year.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.