10 Mysterious Discoveries That Still Puzzle Archaeologists

By Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, 13 February 2017.

By Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, 13 February 2017.

Without archaeological puzzles, researchers wouldn’t have much of a career. Luckily for archaeologists, known objects turn up where they shouldn’t while unknown objects sometimes surface as one-of-a-kind, enormous structures built with dedication but no clear purpose. Civilizations may abandon advanced cities for no reason, and sometimes, there are even unusual treasures of gold.

10. The Riddled Jar

Photo credit: Live Science

A clay vase at a Canadian museum holds more questions than its 180 pieces. Once restored, the true novelty of the pot surfaced - it was created with holes.

Storing food or fluids in something like this would be a bad idea. A hole piercing the bottom also ruled out its usage as a type of lamp, and it doesn’t resemble any known ancient animal containers.

Archaeologists from the Museum of Ontario Archaeology consulted Roman pottery experts, but nobody recognized it. Another mystery is how the vessel arrived at the museum. It may have been dug up in the 1950s from a London World War II crater in an area that was Roman territory 1,800 years ago.

The storage room in which it was found also contained items from Iraq’s ancient city of Ur dating back 5,000 years. Whether from Britain or Iraq, there is no other object like it.

9. The Alaska Artifact

Photo credit: io9.gizmodo.com

In 2011, a team from the University of Colorado was researching prehistoric climate change when they stumbled upon an unusual artifact. The focus site was a 1,000-year-old Eskimo settlement at Cape Espenberg, Alaska.

Centuries older than the house in which it was found, the bronze object resembled a tiny belt buckle. Remarkably, it appears to have been made in a mold. If so, it’s the only ancient artifact of cast bronze to come from Alaska.

The item, a broken ring fastened to a rectangular frame, had a leather strap attached. Radiocarbon dating placed the leather at around AD 600 but doesn’t necessarily reflect the metal’s age. Since bronze wasn’t worked in Alaska, it had to have come from somewhere else.

Most likely manufactured in East Asia, the bronze could have reached the Inupiat Eskimos through trading and been passed down through the generations as a valuable heirloom. Researchers still can’t figure out what either continent supposedly used it for.

8. Tongue Of Stone

Photo credit: The Guardian

In Britain during the third or fourth century, a village performed a bizarre burial. In 1991, archaeologists digging at the site in Northamptonshire were intrigued to find only one of the cemetery’s 35 bodies buried face down.

This smacked of an unfavored status within the community, but the position wasn’t that uncommon. What made history was the man’s mouth. Infected bone proved that the tongue of the man, who was in his thirties when he died, had been amputated and replaced with a flat rock.

Such mutilation is unknown in the archaeological records and could be the first encounter with a new practice or perhaps punishment. There are no known Roman laws about cutting out tongues, but other Roman Britain graves do contain corpses completed with objects. Most are missing heads replaced with pots or stones.

Experts speculate that replacing the tongue with something was meant to kindly complete the man or perhaps, not so kindly, to keep him from ever being whole again.

7. The Jordan Wall

Photo credit: Live Science

In 1948, a British diplomat flying over Jordan noticed a wall cutting across the countryside. This started a mystery that stands to this day. Now called “Khatt Shebib,” the ruins measure 150 kilometers (93 mi) long. The wall was constructed in a north-northeast to south-southwest direction, bears the remnants of about 100 towers, and has sections that branch off or run parallel to each other.

Researchers don’t know who the masons were or what the structure was supposed to keep in - or out. Even in its heyday, it was too short and narrow to keep out a barbarian horde. It was 1 meter (3 ft) high and half that in width. To the west, ancient agriculture is more evident and this tentatively suggests a barrier between farmers and herders.

Khatt Shebib’s original purpose remains lost. Guessing the age of the megastructure isn’t easy, either. All archaeologists can test is pottery left behind, and these pieces date back to AD 750–312 BC.

6. Mystery Coins

Photo credit: abc.net.au

The initial discovery didn’t elicit much excitement. In 2016, 10 coins turned up during the excavation of an ancient Japanese castle. Researchers at the Okinawan site thought that the coins were modern, dirty, one-cent coins from US soldiers, thousands of whom reside on the island chain.

A good wash revealed the coins to be foreign but ancient and minted sometime between AD 300–400. This caused such disbelief that Japanese experts initially suspected that the coins had been hidden as a hoax at Katsuren Castle, a World Heritage Site built during the 13th–14th century.

After dismissing that idea, the experts scanned the disks and detected Roman figures and letters on the surface. The solution isn’t as easy as suggesting a link between the two cultures.

Archaeologists don’t believe there was direct contact between Katsuren Castle and the Roman Empire, leaving open the questions of why and how the bronze and copper coins ended up in Okinawa. East Asian merchants didn’t use Western money, either.

5. The Karakiz Lions

Photo credit: Live Science

A resident from the Turkish town of Karakiz alerted scientists in 2001 to an ancient quarry nearby. Prowling in the quarry was a life-size lion sculpted from granite. The lion was once attached to a second cat, but local belief that monuments hold hidden treasure made looters dynamite them apart. Only the one lion survived intact.

The 3,200-year-old creature belongs to a time when the Hittite Empire controlled the region and the Asiatic lion (now extinct in Turkey) was still around. A second lion statue was found to the northeast of Karakiz and was made by a different artist. Its partner had also been blown off.

The Hittites were the undisputed creators, but why carve such monster-sized lions? Both statues originally weighed five tons each. As transporting the colossal cats too far away would have been madness and water sources were sacred to the Hittites, one theory suggests that the lions were meant to become a monument at a nearby spring.

However, evidence of a Hittite presence in the area that matches the age of the lions remains elusive.

4. The Danish Spirals

Photo credit: Smithsonian Magazine

Every amateur archaeologist dreams about finding the big one. A few years ago, it happened to a pair of hopefuls when they buzzed a field in Denmark with metal detectors - and got their hands on some gold.

The four large rings prompted experts to browse the same field, situated next to the island town of Boeslunde, in the hope of finding more Bronze Age artifacts. What they discovered exceeded their wildest expectations.

Not only was it more gold from 700 to 900 BC, but the number of artifacts didn’t stick to a measly four. Spirals, thin as hair and about 2.5 centimeters (1 in) long, turned up in a cache numbering 2,000 curls.

Found together between fur and wooden fragments, the treasure was probably buried in a luxurious box. What the spirals signified or were used for produced many imaginative theories, but the main suspects include ritual objects sacrificed in the field or clothing accessories.

3. The Jerusalem Vs

Photo credit: yahoo.com

There is a site so mysterious in Jerusalem that archaeologists don’t know what to make of it. Located in the eastern part of the city, rooms are molded from the oldest bedrock in Jerusalem.

Recently, three furrows were found carved into one of the limestone floors. Perfectly V-shaped, the patterns have a depth of 5 centimeters (2 in) and measure 50 centimeters (20 in) long.

Once again, pottery pieces hint at when the complex was last used - around 800 BC. But anonymous hands cut the shapes 3,000 years ago at the earliest. The purpose of the Vs defies identification. However, the environment is not without interesting clues.

The rooms were part of a superbly engineered stronghold constructed around Jerusalem’s only natural spring. Another room held a standing stone with markings reminiscent of some pagan religion, the only one of its kind found in the city. A 100-year-old map, created by a British explorer, also shows a “V” symbol in an underground tunnel not yet explored in recent times.

2. The Missing Residents

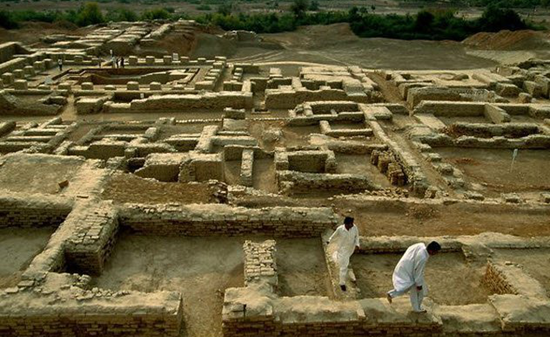

Photo credit: National Geographic

It’s hard to believe that a culture leaving entire cities behind cannot be identified. Now referred to as the Indus Valley civilization, this culture appeared 4,500 years ago and was responsible for the baked-brick ruins of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro in Pakistan.

The people flourished for 1,000 years, traded with nearby Mesopotamia, and had advanced urban planning. Mahenjo Daro is a testament to this fact. Almost every home had proper drainage and a bath, the streets formed an organized grid, and the city itself had a complicated system to control water. This included multiple wells and a large, watertight pool.

There are no signs of royal or religious buildings. Standardized tools and pottery present a more uniform, neat, and orderly sort of society. The city was wealthy, large, and among the most important in the vicinity. Why this flagship trade center died - or the entire Indus Valley civilization for that matter - is an enduring enigma.

1. The Golan Structure

Photo credit: Reuters

It’s been called one of the most mysterious structures in the Middle East. The ancient stone monument was first noticed from the air sometime after 1967. Archaeologists doing a survey over Golan Heights, a piece of land sandwiched between Syria and Israel, noticed five circles flowing inside each other.

The outermost ring was a staggering 152 meters (500 ft) wide. Ground excavations determined that it was 5,000 years old and a contemporary of the famous Stonehenge in England. Almost resembling a labyrinth, the Golan structure consists of small stacks of basalt rocks with a combined weight of over 40,000 tons.

At the center rests a huge burial chamber. But apart from being a grave, it might have had some astrological purpose, too. Researchers found that both annual solstices align with gaps in the walls. The original builders and their intent will perhaps never be known, but the stacking started around 3500 BC and sporadically continued over the next 2,000 years.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.