In the intelligence community, "tradecraft" refers to agents' advanced espionage tactics. That meant creating clever disguises, conducting surveillance, using concealments, procuring secret information and exchanging secure messages with other agents.

"Spies can be ingenious in the way that they communicate," said Peter Earnest, executive director of the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC. He cites miniature dots containing text that came to prominence during World War II. "Somebody can still use that kind of technique."

From Biblical times until the 20th Century, spy operations were pretty much person-to-person, said former director of the CIA’s Office of Technical Service Robert Wallace. He and historian H. Keith Melton detail such tactics in their books "Spycraft" and "The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception."

Earnest and Wallace share these 10 classic spy tactics gleaned from declassified information.

[Note: The subject of this article, in particular Earnest & Wallace's books, has been revealed in another article by Gizmodo. See my comment below.]

[Note: The subject of this article, in particular Earnest & Wallace's books, has been revealed in another article by Gizmodo. See my comment below.]

1. The Combustible Notebook

What’s an agent to do when caught with compromising notes? During World War II, spies could keep sensitive information in a special Pyrofilm Combustible Notebook, Wallace said. This notebook contained film that would ignite when triggered by a particular pencil. Working like a grenade, the paper would burn and the whole thing would disappear within seconds.

The CIA’s one-time pads of paper were used between agents for secure communication using encryption that’s virtually unbreakable. Once they were used, the pages could be torn off and destroyed.

“After that, we developed water-soluble paper,” Wallace said. “You could take notes on this paper but if you were about to be compromised you could immediately just dump the paper in the toilet or run water over it.”

2. Bugs, Tried and True

During the 1960s, integrated circuits represented a major breakthrough. Before that, transmitters were unreliable and required huge batteries.

“Integrated circuits reduced power consumption, made reliability almost 100 percent, and allowed a reduction in size,” Wallace said. New devices were a tenth the size of previous ones. “That means you could put bugging devices about anywhere you wanted to.”

When U.S. supplies were dropped by parachute into remote jungle areas during the Vietnam War, tiny beacons were attached so that U.S. soldiers could follow the signal, Wallace said. He added that, conversely, spies could carry beacons disguised as a branch or a cane, leave it at a specific location, and then moments later an attack fleet would hone in to hit the target.

3. The 'Dead Drop'

One well-known spy technique called the dead drop involved placing an item or message in a device. An agent then signals to a handler that the drop has been made - in the past that meant marking a signpost or building corner with chalk, Peter Earnest said.

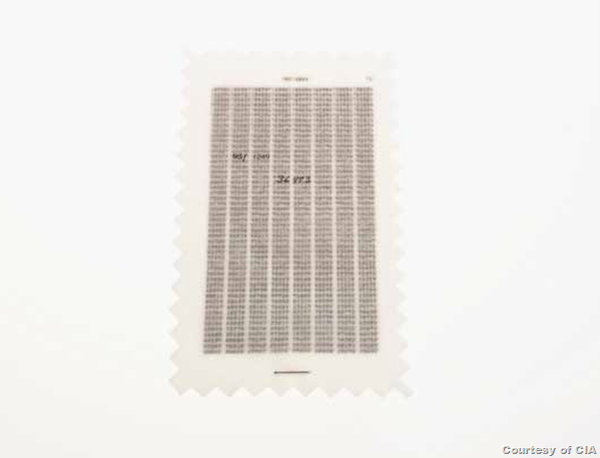

Hollow coins could carry messages. Although the space inside was extremely small, agents could put in a microdot. This micro writing system developed by the CIA in the 1960s and 70s required a high-powered magnifier to read concealed messages.

The most famous espionage case involving a hollow coin occurred in 1953 when a Russian agent inadvertently gave his hollow nickel to a newspaper boy. When the boy dropped the coin, a micro-photograph fell out. It would take the F.B.I. four years to decipher the instructions encoded in the tiny photo.

Micro writing was effective, Wallace said. "It was just very difficult. It had a lot of potential for human error."

4. 'Jack-in-the-Box'

Spies must be ghosts, not poltergeists. To avoid detection, they used maps like this one printed on silk that don’t rustle. The British Directorate of Military Intelligence MI9 issued cufflinks containing tiny compasses during the late 1930s through the mid-1940s.

One tactic Wallace and Melton detail in Spycraft involves using equipment dubbed a “Jack-in-the-Box.” This simple device was a suitcase containing a dummy designed to look just like an agent from the shoulders up. An agent in a car who wants to escape surveillance could wait for a sharp turn, roll out the passenger side, and open the Jack-in-the-Box.

“Even though you are only out of surveillance for five seconds, that was long enough for the officer to roll out of the car quickly into the shadows,” Wallace said.

“Surveillance, looking at the car ahead of them, would still see two people in the car.” In 1982, CIA officers used the device to evade KGB surveillance re-establish contact with an informant.

5. Hidden Surveillance

Clandestine surveillance remains a hallmark of covert operations. In "Spycraft," Wallace and Melton describe cameras hidden in unusual places, audio equipment for listening to conversations through walls, and even a pipe with a receiver so the officer could bite the stem and detect hostile radio communications nearby. In the 1970s, the CIA worked on a mini unmanned aerial vehicle shaped like a dragonfly called the "Insectothopter."

When the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology celebrated its 40-year anniversary in 2003, it revealed a realistic looking robotic catfish dubbed "Charlie." Built in 2000, the device's true mission has never been revealed, but experts think its aim was to sample and test water around nuclear plants and facilities.

“You build in it the necessary filters to take samples,” Wallace suggested. "Then you recover the fish downstream and evaluate those samples."

When the fish was revealed, the Associated Press consulted with a scientist who said the fish was so realistic that predators might target it. Robotic fish have caught on in the academic arena, though. Many institutions now use robo-fish for environmental monitoring.

6. Deliver a Knockout

In the mid-1950s, spies had to be ready to spike a drink in a pinch. Wallace and Melton’s book “The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception” outlines several strategies for dispensing liquids, powders and pills without the recipient noticing.

Glove-wearing lady-spies of the era had a particular advantage with their handkerchiefs, and could sew small containers into them. While lighting someone else’s cigarette, the matchbook could be used to dispense a small tablet into their cup. All in the flick of a wrist.

Wallace said he particularly liked the trick where a standard Number 2 pencil became a tool for delivering a pill or powder - up to 2.5 CCs - simply by manipulating the eraser and the metal band around it.

“It can be a knockout pill, it can be a hallucinogenic,” he said. “I suppose it could be lethal, if you wanted it to be.”

7. Hidden in Plain Sight

Steganography is the practice of leaving a concealed message out in the open. Wallace credited magician John Mulholland for introducing new tactics for this kind of communication to the CIA when he became their consultant in 1953.

“He wrote about how you can communicate,” Wallace said. “He talked about how magicians could communicate when they were doing tricks.” One method for communication was how shoelaces were tied. Connecting them between the holes on both sides of a shoe in different ways signalled certain things such as “follow me” or “I have brought another person.”

Hiding messages in plain sight continues to be an effective tactic. Just look at Al Qaeda. “We have seen that used by the terrorists,” Earnest said. In a case that was just reported, Al Qaeda embedded secret documents in a porn video.

8. The Document Grab

Get that document and get out. Pulling out a small scanner would help today, but spies had to use different techniques decades ago. The CIA Museum now displays this letter removal device from World War II. When inserted into the unsealed gap in an envelope flap, the device grasped the paper and wound it around pincers so it could be extracted without anyone the wiser.

Another way to retrieve documents involved magician’s wax, the kind that temporarily attaches to objects. To use this technique, described in Wallace and Melton’s book “The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception,” first wax was placed on a book cover. In the blink of an eye, the book is used to grab a paper. All the agent had to do is remember to hold the book so that the paper side faces the body or the floor.

9. Short-Range Coded Messages

Long before cell phones, the CIA’s Office of Technical Service was developing what it called a short-range agent communications systems or SRAC. When two officers communicated securely with each other using a SRAC device, they didn't need to risk being spotted in the same location, Melton and Wallace explain in "Spycraft."

An early SRAC device from the 1970s had code names like “DISCUS” and “BUSTER," and resembled a large calculator and contained a keyboard with a stylus for punching in 256 characters, Wallace said.

Using “burst transmissions,” these systems allowed agents to transmit messages across about a quarter-mile range, communicating in bursts through coded messages that were automatically deciphered and displayed. Although the signal could potentially be intercepted, this communication technique represented a significant advancement in tradecraft.

“This meant that you didn’t have to meet an agent to get information,” Wallace said. “You could actually transmit it in real time.”

10. The 'Brush Pass'

That spy film staple, the so-called “brush pass” used to pass documents or a package between agents, can be traced back to the Cold War era. The technique was developed to be used in hostile areas where U.S. agents were under constant surveillance, Earnest said.

“It’s very elaborate,” he said. “You’re staging this but you are arranging for you and the agent to pass each other surreptitiously somewhere.” Highly choreographed, the handoffs took place quickly in alleys, on corners, in subway stairwells.

In late 2009, an elderly couple, Walter and Gwendolyn Myers, was convicted on charges that they had spent several decades spying on the United States for Cuba. Among their tactics, according to the F.B.I., was a variation of the brush pass. Gwendolyn exchanged shopping carts in grocery stores with contacts to pass along information.

[Source: Discovery News. Edited.]

Comment:

The following is an article by Gizmodo with regard to the above-mentioned subject:

Secret CIA Manual Shows Magic Tricks Used By Spies

By Wilson Rothman

During the Cold War, the CIA hired a master magician to teach them deceptive maneuvers. Here are a handful of tricks, recovered from a super secret manual the government thought it had destroyed over 30 years ago.

Our spooky spy friends Bob Wallace and Keith Melton - the guys behind the amazing spy-gadget bible Spycraft - uncovered one of the supposedly incinerated "magic" journals. Their new book, The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception, is in part a verbatim reproduction of that manual, but, thrillingly, it also shares the (declassified) history of CIA trickery from the beginning, including the formation of the double top-secret and sometimes sinister MKULTRA division. MKULTRA was supposed to have been erased from history in 1973, but - in true spy fashion - the few shreds of paperwork that remained ended up telling its whole story.

The discovered manual was penned by John Mulholland, the David Copperfield and/or Blaine of his day. Though Mulholland knew more than anybody since Houdini about pulling fast ones, his challenge was to teach people who were not necessarily pros to pull off tricks in front of an audience that didn't know it was an audience. Perform a lousy trick, and you don't get booed - you get beheaded.

Here Wallace and Melton have kindly shared some newly created illustrations of tricks from the book, CIA sleights you could employ to escape from a water-bottling plant, poison a friend, send messages with your shoelaces, steal single sheets of paper, look dumb, and of course, kill Castro. Not all of the tricks below come from Mulholland's original manual, but they were all devised at Langley, and are all lovingly described in the book - a $16 thrill of a read for anyone with even a passing interest in spyology:

Thanks to Bob Wallace and Keith Melton for sharing their book's illustrations with us. If you'd like to know more about the book, check out its sales page on Amazon (there's a Kindle version too), or visit the authors' new website, CIA Magic.

Comment:

The following is an article by Gizmodo with regard to the above-mentioned subject:

Secret CIA Manual Shows Magic Tricks Used By Spies

By Wilson Rothman

During the Cold War, the CIA hired a master magician to teach them deceptive maneuvers. Here are a handful of tricks, recovered from a super secret manual the government thought it had destroyed over 30 years ago.

Our spooky spy friends Bob Wallace and Keith Melton - the guys behind the amazing spy-gadget bible Spycraft - uncovered one of the supposedly incinerated "magic" journals. Their new book, The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception, is in part a verbatim reproduction of that manual, but, thrillingly, it also shares the (declassified) history of CIA trickery from the beginning, including the formation of the double top-secret and sometimes sinister MKULTRA division. MKULTRA was supposed to have been erased from history in 1973, but - in true spy fashion - the few shreds of paperwork that remained ended up telling its whole story.

The discovered manual was penned by John Mulholland, the David Copperfield and/or Blaine of his day. Though Mulholland knew more than anybody since Houdini about pulling fast ones, his challenge was to teach people who were not necessarily pros to pull off tricks in front of an audience that didn't know it was an audience. Perform a lousy trick, and you don't get booed - you get beheaded.

Here Wallace and Melton have kindly shared some newly created illustrations of tricks from the book, CIA sleights you could employ to escape from a water-bottling plant, poison a friend, send messages with your shoelaces, steal single sheets of paper, look dumb, and of course, kill Castro. Not all of the tricks below come from Mulholland's original manual, but they were all devised at Langley, and are all lovingly described in the book - a $16 thrill of a read for anyone with even a passing interest in spyology:

Source: Gizmodo

More information:

1. The Intelligence Officer’s Bookshelf

2. Studies in Intelligence, Volume 54, Number 1 (March 2010)

IN A NUZZER LIFE I WILL BE A BADASS SPY

ReplyDeletethis has helped me see that i want to be a spy

ReplyDelete