In early February 2017, retired Army Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, the short-lived national security adviser to President Donald Trump, was one of the most influential figures in the U.S. government. But that all changed as soon as the Washington Post published a story containing a bombshell revelation. According to the Post's government sources, the month before Trump took office, Flynn spoke to Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak about U.S. sanctions against Russia - something that Trump's vice president, Mike Pence, denied ever took place [source: Miller, Entous and Nakashima].

Five days after the story published, Flynn resigned [source: Miller and Rucker]. The incident was yet another example of how even the most powerful people in the world have difficulty keeping secrets from investigative journalists.

The U.S. Constitution expressly bars the government from interfering with freedom of the press, which is a sign of how important the nation's founders thought it was to have the news media acting as another check and balance against abuses of power. It's a role that generations of journalists have filled with zeal. They've irked presidents dating back to John Adams, who even convinced Congress to pass a short-lived law making it illegal for newspapers to publish "any false, scandalous and malicious articles" about the government [source: Ourdocuments.gov].

Nevertheless, these oft-maligned journalists have ensured that their readers learned about all sorts of wrongdoing, ranging from mistreatment of mental patients and corrupt practices by giant corporations, to a global surveillance program that kept track of their phone calls. And those investigations often have stopped further abuses and compelled reforms, and sometimes even ensured compensation to victims of misdeeds.

"A huge aspect of journalism - or any journalism worthy of the name - is the act of putting pressure on power," as New Yorker editor David Remnick once explained [source: Malsin].

From the beginnings of investigative journalism in the late 19th century to the present day, here are 10 news media exposés that made a difference.

10. Exposing Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill (1877)

Elizabeth Jane Cochran originally wanted to be a teacher, but after she ran out of money to finish her training, she instead went to work helping her mother run a boarding house in Pittsburgh. One day, she happened to read a newspaper column by a man who insisted that women should stick to domestic tasks such as cooking, sewing and raising children and not work outside the home. She penned an angry letter in response - the editor liked her writing so much that he hired her as a reporter for the women's pages and gave her the pen name Nellie Bly [pictured above].

But Bly wouldn't settle for writing about flower shows and fashion. She went to New York where a newspaper editor offered her an assignment to write about the mentally ill housed at an asylum on Blackwell's Island. Bly daringly feigned mental illness to get inside, and then spent 10 days observing the cruel mistreatment, including beatings and ice cold baths, to which patients were subjected. Her shocking account in the New York World stirred up public outrage, and led to much-needed reforms at the institution.

In the process, Bly also invented a new style of undercover investigative journalism, which would be emulated by generations of reporters [source: PBS].

9. Helping to Bust a Monopoly (1902-04)

In the late 1800s, John D. Rockefeller built the Standard Oil Co. into one of the biggest, richest and most powerful businesses the world had ever seen, one that controlled 90 percent of U.S. oil refining, as well as nearly all the oil pipelines in the nation. Rockefeller achieved that dominance with brutal hardball tactics, forcing smaller refining companies to sell out to him or else face the prospect of having their supply of crude shut off.

In one instance, when another oil company tried to build its own pipeline across Pennsylvania, Standard bought up all the land along the route to block it. Rockefeller even bribed state legislators to assist him in strangling competition [source: CRF].

Standard Oil met its match in a journalist named Ida Tarbell [pictured above], the daughter of a small-time oil producer in northwestern Pennsylvania who'd been harmed by Rockefeller's ruthlessness. As a writer for McClure's magazine, Tarbell spent two years laboriously going through volumes of government records and court testimony. Her 19-part magazine series explained how Standard Oil built its monopoly, dissecting its complex business maneuvers in a way that ordinary readers could understand. Her work sparked a growing public outcry that eventually led to the courts breaking up Standard Oil in 1911 [sources: PBS, King].

8. Confronting McCarthyism (1952-54)

In the years after World War II, Sen. Joseph McCarthy [pictured above], a Republican from Wisconsin, capitalized upon public fear of the Soviet Union to stage a search for communist sympathizers in the government, the military and other parts of society. McCarthy's shrill charges - such as his claim that he possessed a list of 205 State Department employees who were communists - often were based upon thin evidence, but they still ruined lives and careers [sources: Friedman, History.com].

McCarthy's witch hunt roused CBS News journalist Edward R. Murrow - who saw him as a threat to civil liberties - into action. In 1954, Murrow and his producer, Fred Friendly, put together a half-hour episode of Murrow's program "See it Now," devoted to exposing McCarthy's abuse of his power. In doing so, they utilized powerful evidence - excerpts from McCarthy's own statements, whose contradictions and inaccuracies they then highlighted.

In those days, a federal rule called the Fairness Doctrine required CBS to offer equal time to McCarthy. But when the broadcast ended, the phone calls, letters and telegrams that inundated CBS ran 15 to 1 in Murrow's favor. It was the beginning of the end for McCarthy, who was further exposed in televised Congressional hearings, and then censured by his Senate colleagues [source: Friedman].

7. Exposing the My Lai Massacre (1969)

In 1968, U.S. Army soldiers slaughtered hundreds of unarmed civilians in the Vietnamese village of My Lai. The following year, a freelance journalist named Seymour Hersh got a tip from an antiwar lawyer about the war crime. Hersh, who previously covered the Pentagon for the Associated Press, worked one of his former military sources, who identified Lt. William Calley as being involved in the massacre [source: Hersh].

At a library, Hersh found a newspaper brief saying that Calley had been charged with murder. Hersh then tracked down Calley at Fort Benning in Columbus, Georgia, and managed to get an interview with him. Hersh then traveled around the U.S. finding other soldiers and piecing together the story of the atrocity [sources: Hersh, Pilger].

But getting the explosive story published wasn't easy. After both Life and Look magazines turned down a chance to publish Hersh's articles on My Lai, he finally took them to Dispatch News Service, a small antiwar wire service in Washington [source: Hersh]. But after newspapers picked up Hersh's story, it shocked the national conscience. President Richard Nixon, who publicly condemned the massacre but reduced Calley's life sentence to three years of house arrest, later wrote in his memoirs that the incident undermined his efforts to build support for the war [sources: Corley, PBS].

6. Publishing the Pentagon Papers (1971)

In 1967, the Johnson Administration commissioned a secret study, entitled "History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy." The 7,000-page document laid out in scandalous detail the blunders and miscalculations made by the U.S. government in the Vietnam War, including ignoring intelligence assessments and backing corrupt leaders with little support from the Vietnamese populace. Nobody outside the government might have ever seen it, except that RAND Corporation researcher Daniel Ellsberg [pictured above] - frustrated that the report was being ignored - finally gave a copy to New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan.

The Times published the first installment of a series based upon it in June 1971. Johnson's successor in the White House, Richard Nixon, was incensed at the leak. He had his Attorney General, John Mitchell, order the Times to stop publishing information from the report and return it, or face prosecution for espionage.

When the Times refused, Mitchell went to court and sought an injunction. That led to a landmark Supreme Court 6-3 decision, which probably had an even greater impact than the scoop itself. It established that under the First Amendment, the government couldn't prevent the publication of exposés, no matter how embarrassing the facts might be [source: Priest].

5. Uncovering a Cruel Government Medical Experiment (1972)

In the 1930s, 600 African-American men - mostly poor and illiterate Alabama sharecroppers - were offered a chance to participate in a U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) research program for people with "bad blood." They would receive benefits that most poor people in those days could scarcely dream of - rides to the clinic, free medical checkups and a promise of stipends to their survivors.

What USPHS didn't tell the men was that 399 of them had syphilis, a fatal infectious disease, and that it actually wanted to study how it progressed without treatment. The government kept up the Tuskegee study [pictured above], as it was called, for decades, even after penicillin emerged as a cure in 1947 [source: Tuskegee.edu].

Finally, a young government researcher in San Francisco, Peter Buxtun, learned of the secret experiment and tipped off a friend who worked for the Associated Press. She, in turn, passed the information along to Jean Heller in the AP's Washington bureau. Heller started researching, and in July 1972, exposed the study's existence and true purpose in a story that ran on the front page of the Washington Star [source: Jones).

The revelation eventually forced the government to pay US$10 million to compensate the patients and their survivors, and Congress held hearings on how to better protect experimental subjects [source: Isenberg].

4. Watergate (1972-74)

Image via WatchMojo/YouTube

If you've seen the movie "All the President's Men," you already know this story. The Washington Post assigned two young, relatively unheralded reporters, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward [pictured above], to dig further into a June 1972 burglary at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington D.C.'s Watergate complex.

The two soon discovered connections between the burglary, the Nixon White House and the president's re-election campaign. Helped by an anonymous source they called "Deep Throat," who decades later was revealed to be FBI deputy director W. Mark Felt, Sr., they published stories showing, among other revelations, that the break-in had been financed through campaign contributions, and that Watergate was part of a sprawling conspiracy of political espionage and "dirty tricks" to ensure Nixon got a second term.

Nixon still won re-election, but the Post's revelations helped lead to a Congressional investigation which, in turn, exposed the existence of secret recordings of White House meetings. Those tapes implicated Nixon in efforts to cover up the conspiracy, and in August 1974, he became the first U.S. president to resign [source: Britannica.com].

As Woodward and Bernstein wrote in 2012, "Watergate was a brazen and daring assault, led by Nixon himself, against the heart of American democracy." Without their reporting, he might have succeeded.

3. Shining a Light Upon the AIDS Epidemic (1987)

As managing editor of the school newspaper at the University of Oregon in the early 1970s, Randy Shilts made a bold, courageous move for the times: He openly declared that he was gay.

After graduation, Shilts eventually got a job at the San Francisco Chronicle, just as a mysterious new menace called AIDS was just starting to ravage the city's gay community. He was one of the first journalists to grasp the significance of AIDS, and how it would become an important national issue. He persuaded the newspaper to let him cover AIDS and turn it into a fulltime beat. "Any good reporter could have done this story," he once explained. But Shilts had a personal incentive as well, because people he knew were dying of the disease.

Shilts' reporting for the Chronicle eventually became the basis for his 1987 book, "And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic," which indicted the Reagan Administration, the healthcare system and even some gay organizations for not doing enough to deal with the disease's spread. Shilts' book, which spent five weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, helped change attitudes about the disease, which he eventually died from in 1994 [source: Grimes].

2. Exposing a Sex-Abuse Cover-up (2001-02)

Image via Phil Saviano Channel/YouTube

Back in 2001, Boston Globe columnist Eileen McNamara wrote a scathing column about a local Roman Catholic priest, Rev. John Geoghan [pictured above], who was a defendant in a civil lawsuit brought by 25 men who accused Geoghan of raping them as children [source: McNamara]. The newspaper's new editor, Martin Baron, read the column and asked the newspaper's Spotlight investigative team to launch a wider probe of pedophile priests and what the church leadership had known about their crimes.

The Spotlight reporters went after the case with zeal, publishing more than 600 stories [source: Boston Globe]. Their initial article, published in January 2002, laid out in heartbreaking detail how Geoghan allegedly had molested more than 130 children at a half-dozen parishes over three decades - and how archdiocesan officials had failed to stop him, even though they had "substantial evidence" of his predatory tendencies [source: Carroll, Pfeiffer and Rezendes].

The Globe eventually unearthed evidence of a systematic cover-up of other child molestation cases. The Pulitzer Prize-winning effort led to the resignation of Cardinal Bernard Law, and the payment of billions in damages to molestation victims [source Laporte]. The story became basis of the movie "Spotlight," which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2016.

1. Revealing Massive Government Surveillance Efforts (2013)

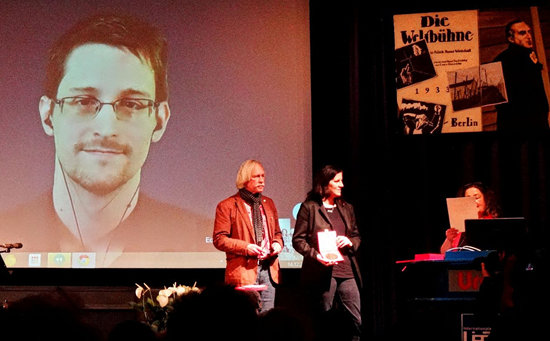

In May 2012, Edward Snowden, a disillusioned information technology contractor for the National Security Agency, told his supervisors that he needed to take some sick leave. Instead, he vanished, taking with him a trove of documents detailing the agency's electronic surveillance efforts around the globe.

Snowden eventually connected with Laura Poitras, a documentary filmmaker [pictured above, center, with Glenn Greenwald]. The first document Snowden sent was an 18-page document detailing how NSA tapped into fiber-optic cables to listen in on telephones around the world - convinced her that this was a bombshell story. But Snowden had much more, including evidence that NSA and big internet companies had collaborated in a secret program called PRISM [source: Harding].

Poitras eventually helped connect Snowden - who thought his revelations might be too big for one journalist - with Glenn Greenwald, a columnist for the Guardian, and Washington Post reporter Barton Gellman. Eventually, both papers won Pulitzer Prizes for their stories. Poitras, who shared in the Pulitzer, also won a 2015 Academy Award for her documentary on Snowden, "Citizenfour" [source: Harris].

The revelations stimulated impassioned public debate about the balance between personal privacy and national security, and led Congress to pass legislation ending the bulk gathering of Americans' phone records, one of the practices Snowden revealed [source: Siddiqui].

Author's Note: Years ago, when I was working as a feature writer for the Pittsburgh Press, it was inspiring to see two of my then-colleagues, the late Andrew Schneider and Mary Pat Flaherty, win a Pulitzer Prize for their investigation of violations and failures in the organ transplant system. I also got at least a sense of the massive amount of hard work - the many hours of interviews, travel to faraway places, and amassing and digging through vast caches of documents - that it takes to get to the truth and tell a shocking story. I think if more people actually saw what real reporters actually do, the news media would have a lot higher public favorability rating than the 32 percent shown in a 2016 Gallup poll.

Related Articles:

More Great Links:

Article Sources:

1. Bernstein, Carl and Woodward, Bob. "Woodward and Bernstein: 40 years after Watergate, Nixon was far worse than we thought." Washington Post. June 8, 2012. (Feb. 17, 2017)

2. Boston Globe. "Key reports from Globe's Spotlight team on clergy sex abuse." March 11, 2016. (Feb. 17, 2017)

4. Carroll, Matt; Pfeiffer, Sacha; and Rezendes, Michael. "Church Allowed Abuse by Priest for Years." Boston Globe. Jan. 6, 2002. (Feb. 17, 2017)

5. Constitutional Rights Foundation. "Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Monopoly." Spring 2000. (Feb. 17, 2017)

6. Corley, Christopher L. "Acts of Atrocity: Effects on Public Opinion Support During War or Conflict." Master's Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, Calif. Dec. 2007. (Feb. 17, 2007)

7. Dews, Fred and Young, Thomas. "Ten Noteworthy Moments In U.S. Investigative Journalism." Brookings.edu. Oct. 20, 2014. (Feb. 17, 2017.)

8. Entous, Adam; Nakashima, Ellen; and Rucker, Philip. "Justice Department warned White House that Flynn could be vulnerable to Russian blackmail, officials say." Washington Post. Feb. 13, 2017. (Feb. 17, 2017)

9. Friedman, Michael Jay. "'See It Now': Murrow vs. McCarthy." State Department’s Bureau of International Information Programs. June 1, 2008. (Feb. 17, 2017)

10. Grimes, William. "Randy Shilts, Author, Dies at 42; One of First to Write About AIDS." New York Times. Feb. 18, 1994. (Feb. 17, 2017)

11. Harding, Luke. "How Edward Snowden went from loyal NSA contractor to whistleblower." Guardian. Feb. 14, 2014. (Feb. 17, 2017)

14. History.com. "1950: McCarthy accuses State Department of communist infiltration." (Feb. 17, 2017)

15. Isenberg, Barbara. "Blowing the Whistle on the Experiment." Los Angeles Times. July 15, 1990. (Feb. 17, 2017)

18. Laporte, Eileen. "The Real Reporters Behind "Spotlight" On Reliving The Facts And Accepting The Fiction." Fastcocreate.com. Jan. 7, 2016. (Feb. 17, 2017)

19. Malsin, Jared. "Seymour Hersh on My Lai and the state of investigative journalism." Columbia Journalism Review. April 1, 2015. (Feb. 17, 2017)

20. McCumber, David. "Pulitzer Prize winner, former P-I reporter Andrew Schneider dies at 74." Seattle Times. Feb. 18, 2017. (Feb. 19, 2017)

22. Miller, Greg; Entous, Adam; Nakashima, Ellen. "National security adviser Flynn discussed sanctions with Russian ambassador, despite denials, officials say." Washington Post. Feb. 9, 2017. (Feb. 17, 2017)

23. Miller, Greg and Rucker, Philip. "Michael Flynn resigns as national security adviser." Washington Post. Feb. 14, 2017. (Feb. 17, 2017)

24. Ourdocuments.gov. "Passed in preparation for an anticipated war with France, the Alien and Sedition Acts tightened restrictions on foreign-born Americans and limited speech critical of the Government." (Feb. 17, 2017)

28. Pilger, John. "Tell Me No Lies: Investigative Journalism and its Triumphs." Vintage Books. 2011. (Feb. 17, 2017)

29. Priest, Dana. "Did the Pentagon Papers matter?" Columbia Journalism Review. Spring 2016. (Feb. 17, 2017)

31. Siddiqui, Sabrina. "Congress passes NSA surveillance reform in vindication for Snowden." Guardian. June 3, 2015. (Feb. 17, 2017)

32. Stelter, Brian. "How leaks and investigative journalists led to Flynn's resignation." CNN. Feb. 14, 2017. (Feb. 17, 2017)

33 Swift, Art. "Americans' Trust in Mass Media Sinks to New Low." Gallup.com. Sept. 14, 2016. (Feb. 17, 2017)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.